|

|

As of late the Roost has been obsessed with pirates thanks to Riley’s love for chanties. Because of this I decided to write a flog post as if Team Echinacea were as a pirate crew. Enjoy!

June 25th, 2018. A storm is brewing. As the crew traveled to the docks where the S.S. Hjelm was stationed we sang some of our favorite chanties like Boys by Charli XCX. Once we arrived at the docks we broke into smaller groups. A group of us, led by Captain Stuart, marked out where our precious purple coneflower treasure was in p1. (Not all of this can be paralleled into a pirate based theme, but I’m trying my best).

Andy standing stoically as the storm approaches. Knowing that the worst is inevitable, but still hoping for the best The storm that was brewing passed over as we headed in for meal time. We were meet with a new crew member named Amy who quickly won us over with brownies (Not sure if pirates ate brownies, but couldn’t think of the equivalent of brownies for pirates). Once our meal was finished, Captain Jennifer took us out to p2 where we also marked where our precious purple coneflower treasure was buried. As the day came to an end, the crew members who lived in the Roost (and Kristen) returned home where we ate a meal prepared by Andy and talked about tales of native bees (Didn’t know how to incorporate our scientific reading club into the story smoothly, but I think that’ll work). Amy also joined us as we shared tales about native bees.

As dusk began to fall upon the sky, I recorded the events of the day in the captain’s log (The pirate version of the flog) before retiring to my quarters and resting for the tasks that tomorrow holds.

After risking their lives to mark the precious purple conflower treasure, crew members began the long journey from p2 back to the docks where the S.S. Hjelm was stationed. The work for the day may be over, but more challenges lie ahead. However, with the camaraderie among the members, there is nothing the crew can’t overcome.

Evan-

The first thing that comes to me when I think about East Riley is definitely the poison ivy. The notorious three leafed plant made me hesitant to get any closer to investigate the site. Fortunately, there were a few Echinacea plants present closer to the side of the road. Both sides of the field were bordered by agricultural fields. The agricultural field facing north was growing soybean while the field facing south was growing corn. When out at the site I didn’t notice any solitary bees flying around, but next time I’m at East Riley I would want to observe how frequently they fly to this specific site even with the large amount of poison ivy present.

Riley-

Nothing is more exciting than arriving to a site that shares one’s name. That being said, I had high expectations for a locale sharing my alias; I anticipated a diverse array of species as well as a slew of budding Echinacea heads. Unfortunately, my wish for high species richness did not come true, but I was lucky enough to spot 8 Echinacea heads. Although the exact land use history of the site was unknown to myself, I could only speculate (with the help of Ruth) that the land was previously used for agriculture due to low plant diversity and a lack of remnant prairie indicator species. My experience at East Riley as one of my first impressions of a non-remnant prairie will leave a lasting impact on me because the difference in plant community composition between it and remnant prairie is so immense. It is amazing to me how years of land use can be summarized by a plant layer on topsoil and how much we can learn from this green blanket.

Ruth –

As the member of our team who had been to East Riley quite a few times, I noted its usual great extent of bare ground from which numerous Echinacea with nicely developing flowering stems were emerging. Here, there is a rather wide (over a meter, I’d say) road edge that is level with the road surface. This edge is frequently scraped by snow plows and other road maintenance equipment. The mature Echinacea, with their deep taproots, tolerate this remarkably well, resprouting over many years. Other species typical of unbroken prairie, like leadplant, are not abundant here and may be less tolerant of the scraping. At this site, we have found many seedlings of Echinacea each year for a decade and have relocated them in subsequent years to monitor their survival and (eventual) flowering. Amy Dykstra led this seedling project and has been working on this dataset this year. I don’t remember such vigorous poison ivy in the past. Important to beware of that patch!!

Ruth draws a map of East Riley while Evan enters site data onto his Visor.

The year is 1300 CE. Steven, a viking explorer, has just landed on the shores of the land that would one day become Kensington, Minnesota. Steven and his crew pull their longship ashore on the banks of the vast Southern Canadian Sea, weary from their long journey. Although Steven would never see how dairy, corn, and soybeans would feed the world of his progeny, Steven saw in this landscape the potential for a land of vast prosperity. In the first few months, Steven lost most of his crew to a frog-borne parasite, now known exclusively for its adverse health effects in dogs. Steven learned the lay of this new land but often struggled. He was drawn back to his homeland after many years of documenting the landscape. Steven took with him a new appreciation for the beauty of discovery, and respect for new lands. Though most traces of Steven’s visit are lost, the Kensington runestone documents Steven’s journey into the unknown.

In the years following Steven’s journey, this majestic Southern Canadian Sea receded further to the north, eventually becoming what we know today as the boundary waters. As the soil dried, the sea floor served as a mineral-rich substrate for the colonization of new seeds. This new community of plants (dominated by grasses, forbs, and legumes) became the tallgrass prairies we know and love. Many people and animals have come to appreciate the prosperity of this verdant land. The spot on which Steven first stepped foot on North American shores is known today as Steven’s Approach.

Today, Steven’s Approach provides scientists associated with the Echinacea Project an opportunity to study how small plant populations persist in fragmented habitats. The site is comprised of two small remnant prairie patches located along Wolly Lake Road near Kensington, Minnesota. Most of the site is dominated by non-native plants. Invasive plants like these often make it difficult for native plants to compete for resources and space. This ecological consequence of small habitat sizes may impact the native plants at this site. Steven’s Approach only had one flowering Echinacea individual. What are the chances for reproduction and survival when your population is 1? This single plant is dependent upon pollinators for spreading its genetic material. How close is the nearest Echinacea individual? Will this individual plant at Steven’s Approach be able to spread its genes onto the next generation? This plant may struggle to survive and reproduce in the coming years.

Perhaps Steven existed, perhaps he did not; regardless, we hope that you were able to see the value of Steven’s journey. Discovery, growth, and a willingness to live with an open mind were key to his success. Our own growth this summer will be a lot like Steven’s. Like Steven, we will approach this new experience with a willingness to grow. We will learn more about ecology and evolution in fragmented habitats. We will take the knowledge we gain from this summer back with us to our own institutions in the fall. While we seek knowledge about the world around us, we will really come to know ourselves.

Why did the bee cross the road? In order to answer this question first consider the road. On the first day working with the Echinacea Project, we (Zeke, John, and Brigid) visited the Around Landfill site. The aforementioned road passes through this Around Landfill site, which coincidentally, is located around a landfill. On either side of the road, C4 warm season plants and legumes grow. Alfalfa and Yellow Sweet Clover pepper the roadside, breaking up the green with flashes of purple and yellow. Small Echinacea buds hint at flowers to come. Corn dominates the landscape farther from the road. Cattle once grazed on one side of this road, as evidenced by a barbed wire fence.

There wasn’t always a road to cross. Before the road, a sea of uninterrupted prairie swayed as far as the eye could see. At this time, before the road broke the continuity of the prairie, the bee had no need to cross the road. Now, grasses, flora and legumes must straddle the road. In order to bridge this divide and visit flowers, the bee must now cross the road.

But can bees cross the road? Consider this question from the perspective of a bee. A bee’s umwelt is quite different from that of humans; bees have a short field of vision as well as the ability to see the UV spectrum of light.

We all sat on the roadside at this site, wondering if bees were indeed able to cross the road. Then, just when we asked this question aloud, a butterfly serendipitously flew across the road, as if in answer. If a butterfly can cross, we supposed that a bee can as well.

But will the bees be able to cross the road in the future? Given rapid expansion of cities, it is likely that the road will wide, creating a world for cars and not bees. Getting to ‘the other side’ could prove a much more daunting task in the future.

Now that my time at the garden is coming to an end, I wanted to include a summary of the projects that I’ve been working on. These three projects include organizing solitary bees that have been collected from yellow pan traps in Minnesota over the past summer, identifying pollen on Echinacea styles and recording the behavior of solitary bees inside emergence traps.

Last summer, several yellow pan traps were placed on the sides of roads in Minnesota in hopes of collecting solitary bees. Once they were collected, each solitary bee was pinned and tagged with a label that included the date, trap number, location, and an ID code. Before logging any of the information into the Roadside Pollinator spreadsheet (this keeps track all of the solitary bees that were collected over the summer in the pan traps) I grouped the specimen together by  taxon. I started grouping more recognizable groups together like Agapostemon virescens before looking at more difficult specimen. Once all grouped together, I would enter the information listed on the label into the spreadsheet. I started with the specimen at the top left corner and worked my way to the bottom right corner of the box. I did it this way to make it easier for anybody to match the information listed in the spreadsheet with that particular specimen in the collection. I was not able to enter every specimen into the spreadsheet, but I did learn key characteristics that will help me distinguish solitary bees when I’m out in the field in Minnesota this summer. taxon. I started grouping more recognizable groups together like Agapostemon virescens before looking at more difficult specimen. Once all grouped together, I would enter the information listed on the label into the spreadsheet. I started with the specimen at the top left corner and worked my way to the bottom right corner of the box. I did it this way to make it easier for anybody to match the information listed in the spreadsheet with that particular specimen in the collection. I was not able to enter every specimen into the spreadsheet, but I did learn key characteristics that will help me distinguish solitary bees when I’m out in the field in Minnesota this summer.

Another project that I worked on while at the garden was looking at images of Echinacea styles to see whether or not foreign pollen grains were present. Every style had three images at varying depths. This was done to get a better look at the pollen present (or absent) on the styles. Over the three weeks that I’ve been at the garden I’ve checked 646 styles for foreign pollen and since each style has three different images, I’ve looked at over 1930 images. You may think I’m an expert by now at recognizing foreign pollen, but I’m still very uncertain about what’s present. However, thanks to Tracie, a system was set up to gauge this uncertainty of whether or not there is foreign pollen present.

Even though it sounds like I spent most of my time in the lab, I was actually outside collecting solitary bees and testing them in emergence traps majority of the day. Once I come into the lab in the morning, I immediately grab the bee-catching net and plastic vials that are in the lab. I also grab my lucky bucket hat before heading out. I head over to the prairie area in the gardens and try to look for areas that have a dense population of golden-rods. When I first started out this summer I had trouble catching bees, but now with a few weeks of experience underneath my belt I’m able to catch solitary bees with and without the net. I’m able to catch the bees without the net by closing the top of the vial around it while it’s resting atop of flowers. Once I’ve caught a few bees (I catch about four to six solitary bees per day) I head back to the lab and grab the emergence traps. I return back to the prairie area and set up a trap on a south facing slope in order to record the behavior of the bee. I either record footage of the bee or record my observations in a notebook, it all depends on how well I’m able to see through the trap. Once I have my observations/film for the day I return back to the lab and share my findings with Stuart.

On a typical day I would be rotating through these three projects, but I’ve also been able to sit in on a few presentations, including a master thesis defense and a PhD seminar. While at the garden I’ve learned many skills that I hope to continue using this summer in Minnesota!

Today will mark the completion of my first work week here at the garden so I just wanted to summarize some of the tasks I’ve been doing for the past five days. The start of the week was dark and gloomy, like any typical Monday, but it was accompanied with a downpour that left me soaked when walking to the Plant Science Center from the train station. Because of the weather I wasn’t able to go out and collect any solitary bees to use in the emergence traps for Kristen’s experiment. Instead I cleaned a few Echinacea heads, identified foreign pollen and continued to develop my skill for identifying the different bees native in Minnesota. Tuesday was a little better. I wasn’t completely soaked, but it was still cold on the walk in that morning. Once again I wasn’t able to go out and collect any bees. However, I was able to identify a large portion of the pollen slides. Also, I found my own method of cleaning Echinacea heads. I use a smaller pair of tweezers to pluck out the achenes and use the larger pair to brush out any that I may have missed. It’s not the fastest way of cleaning, but I think it’s pretty effective.

Wednesday it was finally warm enough to go out and collect solitary bees. My first day out catching solitary bees didn’t go so well because I didn’t catch any. I did catch a few hoover flies and honey bees and recorded their behaviors in the emergence traps. Before leaving that day, Tracie, Kristen and I set up an emergence trap in the prairie area to see if we would catch anything. The next day when I checked the trap we had a few specimen in the trap. They weren’t bees, but now we know that the traps work! Later that day I was able to collect some solitary bees and record their behavior. Today I was able to catch more solitary bees and record their behavior. This time around I decided to film their behavior in the emergence traps using my phone which I will continue to do. I was able to take a video of a Ceratina that I collected, but because the video size is too large I can’t upload it here. However, I was able to upload another recording of an unidentified solitary bee in the emergence trap. I wasn’t able to put the bee into a vial and identify it back in the lab once it crawled from under the trap, but hopefully I’ll catch another one and identify it next week!

Greetings floggers!

The interspecific competition has offered the following results:

- Interspecific competition of growth rate is greater for Bromus kalmii with Elymus canadensis compared to intraspecific competition of Bromus kalmii at this stage of growth.

- The growth rate of interspecific competition for Elymus canadensis with Bromus kalmii demonstrated a negligible change compared to intraspecific competition.

*To view the full write up click here: Interspecific comp.

Fig 1: Vertical black line on each histogram indicates the mean value for each treatment (E. canadensis vs B. kalmii, E. canadensis vs E. canadensis, B. kalmii vs E. canadensis, or B. kalmii vs B. kalmii) of interspecific competition and intraspecific competition. (F) indicates the focal plant. Likewise, my spring semester internship has concluded as well. This experience has been an amazing and immersive learning opportunity. Within the past week, since the end of my internship, I’ve noticed a shift in the way I think. I’ve started observing plants, not just for their beauty, but also for their seed composition and amazing structures. I have found an appreciation and curiosity for the conservation of our native species and the ecosystems they take part in.

The CBG is a wonderful place that cultivates the excitement of science. Whatever the future holds, I will maintain the same attitude as I have during this experience. From day one, I knew I was in a special place and needed to absorb every moment of it. This internship has truly exceeded my expectations.

In closing, I’d like to thank Stuart and Tracie for their guidance, support, and exposure to a fascinating study of plant science. I also would like to thank them for transplanting my grasses to the prairies of Minnesota, where they can grow to their full potential 🙂

E. canadensis transplanted to the MN prairie by Tracie Hayes and Stuart Wagenius. Grown from seed by Danielle Oilschlager 🙂 Sincerely,

Danielle

Do you want to germinate some seeds? A while ago Andrea Kramer recommended four resources to find out about seed germination. I’m copying them here:

1. A good place to start with when you are working with a new species: http://www.charlesgwillis.com/baskin-dormancy-database/ This database goes along with the 2014 Baskin seed book, below. It is free but requires sharing your contact info.

2. The book: Baskin, C. and J. Baskin. 2014. Seeds: Ecology, Biogeography, and Evolution of Dormancy and Germination. 2nd ed. Academic Press, New York.

3. The Royal Botanic Garden Kew has a Seed Information Database: http://data.kew.org/sid/

4. A handy paper with guidelines for a “move-along” experiment: Baskin, C. C., and J. M. Baskin. 2003. When Breaking Seed Dormancy Is a Problem: Try a Move-along Experiment. Native Plants Journal 4:17-21.

Bonus:

5. Prairie Moon Nursery has a Cultural Guide that lists germination requirements for hundreds of Midwestern U.S. species. It’s a big excel spreadsheet that you can access from this page….

https://www.prairiemoon.com/blog/resources-and-information

6. For germinating Echinacea angustifolia, we use a modified version of the protocol developed by Feghahati & Reese in 1994. We don’t use fungicide, but otherwise stick pretty close to their recommendations. If you use this protocol, please cite this paper.

Over the past few weeks, Elymus canadensis and Bromus Kalmii have taken to the plots for a battle of resources. When I initially began this experiment, I hypothesized that Panicum virgatum would take the lead, since it develops a ribosomal root system and is known to be an aggressive prairie species. However, out of 500 seeds, only 1 P. virgatum has germinated and sprouted. For that reason, I’ve decided to eliminate P. virgatum from the data analysis. Although, I have planted the lonely P. virgatum so that it can later be transplanted to the prairies of Minnesota. I later suspected that E. canadensis would take the lead in sprouting. However, B. kalmii has currently overthrown the number of germination/sprouting. There are still a few weeks to go with this experiment before analyzing the data collected on height. With that said, it could go either way. The grasses are growing taller and faster than any of us expected. I take measurements weekly and can already conclude that competition is occurring. The leading height in each treatment varies, indicating that one of the species is achieving more resources than the other. More updates and photos to come!

Sincerely,

Danielle

Competing species – 2 seedlings to a cell  Bomus Kalmii germinating/sprouting in the agar-petri dish  The one and only germinating/sprouting Panicum virgatum

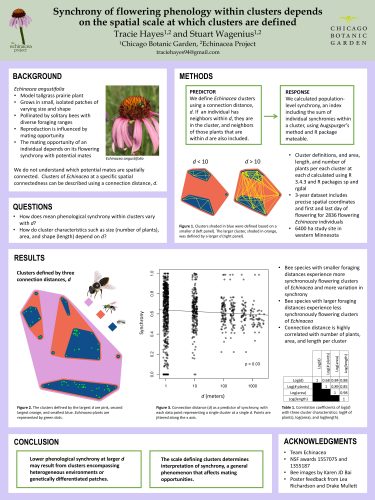

Hi flog! This past weekend I presented my cluster/spatial scale research at the Midwest Ecology and Evolution Conference at the Kellogg Biological Station. Check out my poster!

Synchrony of flowering phenology within clusters depends on the spatial scale at which clusters are defined – Tracie’s MEEC 2018 poster  Tracie with her poster at MEEC 2018

|

|

taxon. I started grouping more recognizable groups together like Agapostemon virescens before looking at more difficult specimen. Once all grouped together, I would enter the information listed on the label into the spreadsheet. I started with the specimen at the top left corner and worked my way to the bottom right corner of the box. I did it this way to make it easier for anybody to match the information listed in the spreadsheet with that particular specimen in the collection. I was not able to enter every specimen into the spreadsheet, but I did learn key characteristics that will help me distinguish solitary bees when I’m out in the field in Minnesota this summer.

taxon. I started grouping more recognizable groups together like Agapostemon virescens before looking at more difficult specimen. Once all grouped together, I would enter the information listed on the label into the spreadsheet. I started with the specimen at the top left corner and worked my way to the bottom right corner of the box. I did it this way to make it easier for anybody to match the information listed in the spreadsheet with that particular specimen in the collection. I was not able to enter every specimen into the spreadsheet, but I did learn key characteristics that will help me distinguish solitary bees when I’m out in the field in Minnesota this summer.