The tallgrass prairie once occupied vast expanses of land across America’s heartland. Today, it is among the most threatened and least protected habitats in the world. Each year, parts of the tallgrass prairie continue to be lost to agriculture and development making the conservation and protection of this system of utmost importance.

Native bees are the most abundant and most important pollinators in the tallgrass prairie. The bees that we study for this project are called solitary bees. They are different from honeybees in that they are native to North America. They are also different from bumblebees (where many genera are native to North America) in that they do not form a colony and build their nests individually.

We know a lot about the kinds of things bees like to eat (pollen and nectar) and their foraging behavior. However, most solitary bees spend the majority of their life in their nests, yet we know so little about what conditions are suitable for them to build their nests. In the tallgrass prairie, over 80% of bees are solitary, ground-nesting bees. We have a lot to learn about the kinds of habitat suitable for them to build their nests in.

We know some things about what ground-nesting bees may like. Evidence suggests they might like sandy soil, bare ground, and well-drained, south-facing slopes. However, we don’t know what bees in the tallgrass prairie may like for their nesting habitat conditions as most of these studies have been done across other ecosystems.

Much of the prairie has been changed from its original condition. We call the history of this condition “land-use history.” I am interested in how the history of the land may determine where bees build their nests in the ground. Some common types of land use history are remnant prairies which are pristine habitats with untilled soil, prairie restorations which are plantings of prairie plants with disturbed soil, and old fields which are fields leftover from agriculture that may have been tilled or grazed.

Using emergence traps, we moved traps everyday for a total of 1,440 across the season. We caught 110 ground-nesting bees in traps across 24 sites this summer. I placed traps at 8 different locations, each with three different land types at each location (remnant prairie, prairie restoration, and old fields). We found that the most bees nest in the prairie (40), while restorations and old fields have the same numbers of nesters (35). While land use is not good at determining bee nests, we did find that the location and land use when combined are both important in determining where bees nests.

I also placed pan traps at all 24 sites and caught 564 bees. Pan traps were colored blue, white, and yellow to attract a diversity of foraging bees at every site. We will use these bees to compare the foraging and nesting communities at each site.

I also measured many microhabitat characteristics of the soil and vegetation at some of the traps. We found that bare ground is a good predictor of where bees build their nests. We also found that the soil texture, especially the amount of silt and sand help determine where bees nest. A diverse plant community with lots of native plants is also a good predictor for bee nests.

We still have a lot more work to do to determine where bees are building their nests. Our next steps are to identify all the bee specimens caught in ground nests and in pan traps. Once specimens are identified, we can learn more about the species specific results for ground nesting bees.

Two of the tents used to capture bees out in the field

Start year: 2018

Location: Hegg Lake Wildlife Management Area restoration, Riley, Aanenson, East Elk Lake Road, and other non-project sites

Overlaps with: Pollinators on Roadsides

Physical specimens: 674 bees were brought back to CGB and are currently being pinned and photographed by Mike Humphrey. Soil samples were collected from every location where bees were caught + a random sample from other traps.

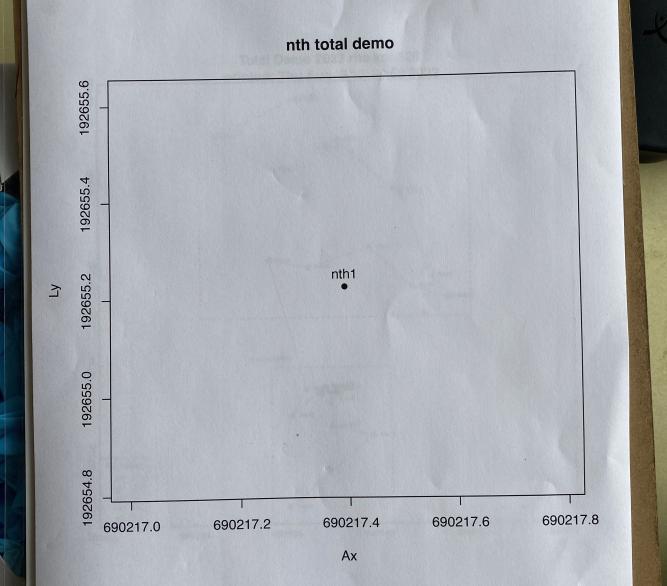

GPS points shot: We shot points for all trap locations. Ask/email Kristen for this data.

Products: This work is part of Kristen’s Master’s thesis

Previous team members who have worked on this project include: Anna Vold (2018)

Thanks so much to help from Team Echinacea 2018, especially Anna Vold who helped measure soil texture. Also many thanks to Emily Staufer from Lake Forest College who processed bees from HFW, and Mike Humphrey who has pinned some bees from this project.