|

|

Welcome back to the next installment on this series of planting seeds for our new experimental plot. If you remember from the last post, I posed the question – do you think that this second planting would have more or fewer seeds than the last one?

More. It was more.

While we planted 800 seeds on Wednesday, on Friday we planted a good 1400 seeds. As you can imagine, this took considerably more time. But luckily, we had even more help! Anne and Priti both came to help with planting. Anne even came up with an ingenious way to use toothpicks to track which head each seed in a plug came from. Now, we have 2200 planted seeds! Seeing as our original goal was 1200 – I’d say that’s not to shabby.

Cotyledons are starting to burst through in our farthest ahead seedling and they are all chugging along at a steady pace. Personally, I love watching these little guys grow and get a lot of satisfaction from knowing that they will grow up to flower some day and be used in experiments for many years to come. That being said, it’s really going to be a monumentous effort to plant all of these guys. Hopefully team echinacea 2019 will be up to the task.

Oh yeah, be on the lookout for bios from Team Echinacea 2019 coming soon!

Anne grabbing a germinated seedling with tweezers  Priti selecting seeds to be planted

Welcome to germination part two! Here, I’ve got an update to what’s been happening with our seeds! Since the seeds in the petri dishes germinated so well, they have been moved in to plugs. Now, I’ve said “moved into plugs” as if it was a simple scoop and dump of seeds into soil. Wrong!

In our first session, we planted exactly 800 seeds into individual pots in a tray. These are called plugs. I stressed that there were exactly 800 because of two facts that line up perfectly:

- We planted every single seed that we found that had germinated, so if 801 had germinated, we would have planted 801 plugs

- plugs come in trays of 200

So hopefully you can now see why that was so great. No need to start that last pesky tray!

Obviously this was a huge job, and while I certainly planted a lot of the seeds (being on my feet for 5 hours was actually a bit of a relief – I much prefer it to sitting), I also had some help! Kathryn planted about 200 of the seeds in the morning, which was a big help.

We plant again in two days. Will we have more or fewer seeds to plant on that day? Stay tuned in!

A planted tray

So it’s been a while since there’s been an update from inside the lab, but that certainly doesn’t mean that nothing’s been happening! Over the course of the last several weeks, we’ve been germinating seeds for the West Central Area Secondary School’s new Environmental Learning Center experimental echinacea plot. And I happy to say that we have many, many seedlings to plant!

Radicals galore! I wont spoil quite yet what ends up happening to all these lovely emerged seedlings – you’ll have to wait for a future flog post to see that. What I will say is that once these little guys get going, they can really grow! Look for more flog posts in the future tracking these guys all the way out into the field.

I have to add that after spending many months working with number regarding echinacea plants, it’s very exciting to be working with the plants themselves. Especially new baby plants! If all goes according to plan, many of the seeds you see here have a very long (and very well recorded) life ahead of them. You get to say that you’ve seen them on the day they were born (are plant’s born? That’s a question for another day)

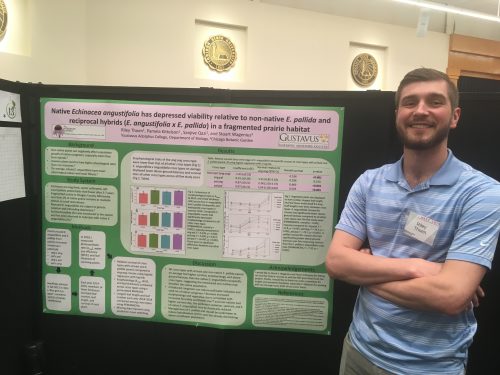

Next up from MEEC we have Riley’s poster about the photosynthetic rates of Hybrid plants in exPt7. Riley collected the data for this project in the summer of 2018, and has been working on aggregating and analyzing since then. The central question behind the research: do Echinacea hybrids between E. angustifolia and E pallida have higher photosynthetic rates than conspecifics?

Riley with his poster Overall (as the title says), Riley found that E. angustifolia may be in trouble if it has to compete with E. pallida. Both the hybrids and conspecific E. pallida plants were more photosynthetically active than E. angustifolia. Additionally, they had higher survival rates. And to put the final nail in the coffin, the only plant that has flowered in exPt7 is an E. pallida plant. All things considered, Riley’s work is crucial to finding out how to protect E. angustifolia from this invasive species!

Click the link bel0w for a full .pdf of Riley’s Poster

echinaceaPoster2_Thoen

Title: Native Echinacea angustifolia has depressed viability relative to non-native E. pallida and reciprocal hybrids (E. angustifolia x E. pallida) in a fragmented prairie habitat

Presented at: MEEC 2019 at Indiana State University in Terre Haute, IN

When: April 27th, 2019

Hello again!

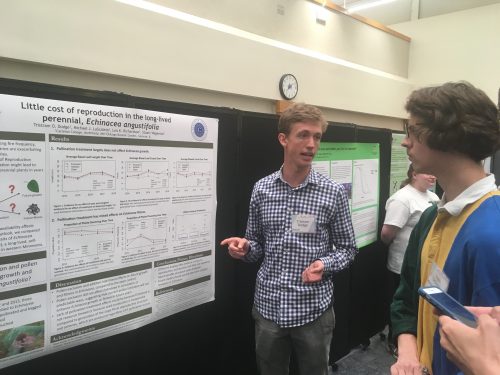

I’m back with more updates from our team trip to Terre Haute for MEEC 2019. Today, I want to show off the incredible pollen limitation study poster presented by Tris Dodge. Tris joined Team echinacea this last November when he was a Carleton Extern at the Chicago Botanic Garden for three weeks before winter break. As an intern, Tris did a lot of work gathering and analyzing data on our pollen limitation study. If you want to learn more about that study, check out our background page. If you want to see the work that Tris did specifically, check out the flog posts that he has written. Tris’s flog posts include a direct link to his poster

In his analysis, Tris found out that creating seeds is basically free for echinacea plants. If they produce a lot of seeds one year, they can produce a lot of seeds the next year as well. This was not what we had predicted! Tris used the data from 7 years of the pollen limitation study to show that plants that had zero reproduction did not turn into big-leafed, multi-head super plants, but instead look exactly the same as those heads that produced many achenes.

Tris presenting his poster to Nate Title: Little cost of reproduction in the long lived perennial, Echinacea angustifolia

Presented at: MEEC 2019 at Indiana State University in Terre Haute, IN

When: April 27th, 2019

A bumblebee on a yellow flower. We use yellow pan traps to mimic these Asteraceae Pollinator diversity and abundance are declining due in part to land use change such as habitat destruction and fragmentation, pesticide contamination, among other numerous anthropogenic disturbances. The extent to which pollinator and native bee diversity and abundance is changing is not well understood, especially within tallgrass prairie ecosystems. Pollinators are important in the prairie and they provide valuable ecosystem services to native plants and to economically important plants used in agriculture.

In summer 2018, we collected bee specimens from 37 roadside sites using yellow pan traps. These sites are located within a gradient of various surrounding landscapes, some surrounded by natural areas, semi-natural areas, agricultural fields, development, or a mixture of the above. IN summer ’17 we sampled over 600+ bee specimens across 8 sampling weeks. IN summer ’18, we captured similar abundances of bees (~450 specimens) collected across 6 weeks. Once specimens are collected, they are stored in ethanol until we are able to pin them. Once specimens are processed, we catalog specimens and keep a record for later specimen identification. Identifying specimens to species requires specific, expert knowledge of the families and genera of native bees and pollinators in this ecosystem.

The goal of this experiment was to repeat a similar study done in 2004 by Wagenius and Lyon, in which they collected information on pollinator abundance and diversity. The aim of the project was to understand how landscape characteristics may influence bee community composition. The information from this project allows us to make comparisons between the pollinator communities collected in 2017, and a similar project from 2004. This information can inform diversity and abundance changes across the 13-14 years and provide valuable insight into native bee declines in this system.

Year started: 2004, rebooted in 2017

Location: Roadsides in and around Solem Township, Minnesota.

Overlaps with: Ground nesting bees (link to come)

Samples collected: Over 450 bee specimens, currently being pinned at CBG

GPS points shot: Locations for each of the pan trap sites

Team Members who have worked on this project include: Steph Pimm Lyon (2004), Alex Hajek (2017), Kristen Manion (2017 & 2018), and John VanKempen (2018). Also, a big thank you to Mike Humphrey who has worked in the lab pinning, processing, and cataloging native bee specimens from the 2017 and 2018 field seasons.

You can find out more about the pollinators on roadsides project and links to previous posts regarding it on the background page for this experiment.

In 2018, we searched for 30 of the original 66 Echinacea hybrid plants. We found 29 Echinacea hybrids… which shows incredibly low mortality! This means that 40% of the original cohort is still alive, with the survival rate this winter of more than 96%! Of the surviving plants, the average leaf count was 2.2 leaves, the longest basal leaf was 14.75cm. These plants are considerably smaller than their exPt9 counterparts, despite being several years older.

This big bluestem made finding these tiny plants pretty hard! This plot was originally developed for Josh Drizin’s experiment with exotic grasses, but 66 hybrids of Echinacea angustifolia and Echinacea pallida were also planted in 2012. In 2011, Gretel and Nicholas Goldsmith performed reciprocal crosses between 5 non-native pallida plants found at Hegg Lake and 31 angustifolia plants in P1. These plants have been revisited each summer since then.

Year started: Crossing in 2011, planting in 2012

Location: Experimental Plot 6, on Tower Road

Overlaps with: Echinacea hybrids — ex Pt 7, Echinacea hybrids — ex Pt 9

Data collected: Status, rosette count, longest leaf measurement, and number of leaves for each plant. Exported to CGData.

Products: Nicholas Goldsmith wrote a summary of the crosses he conducted in 2011. A chapter of his dissertation, which he defended in December, reports on the fitness of hybrids compared to plants of either species.

You can find more information about experimental plot 6 and previous flog posts about it on the background page for the experiment.

In summer 2018, we again measured Echinacea plants in experimental plot 9 at Hegg Lake. These plants are from open-pollinated E. angustifolia plants near the restoration plot with flowering E. pallida plants. ExPt9 includes some hybrid plants, as determined by DNA fingerprinting techniques. The table below shows the number of plants found alive during each search since the experiment started in 2014. Much like last year, the average surviving plant had about 3 leaves. The average longest leaf was 21 cm, 4 cm shorter than in 2017. We suspect that leaves are shorter this year than last year (25cm in 2017 on average) because of a burn in the Hegg Lake WMA. This year we searched for plants once then rechecked every position where we didn’t find a plant during our first search. No plants flowered this year (no flowering plants yet!).

| Year / Event |

Number Alive |

% Original remaining |

% Of previous year |

| Planting (2014) |

746 |

100 |

N/A |

| 2014 |

638 |

85.5 |

85.5 |

| 2015 |

521 |

69.8 |

81.7 |

| 2016 |

493 |

66.1 |

94.6 |

| 2017 |

401 |

53.8 |

81.3 |

| 2018 |

329 |

44.1 |

82.0 |

This experiment comparing the fitness of Echinacea hybrids with pure-bred E. angustifolia and E. pallida will give insight into the possible consequences of non-native E. pallida being planted in restorations in Minnesota, where E. angustifolia is the only native Echinacea to this area of MN.

Most exPt9 plants look like this! Start year: 2014

Location: Hegg Lake Wildlife Management Area — experimental plot 9

Overlapping experiments: Echinacea hybrids — experimental plot 6, Echinacea hybrids — experimental plot 7

Data collected: Rosette number, length of all leaves, herbivory for each plant collected electronically and exported to CGData. Recheck information for plants not found was also collected electronically and stored in CGData.

You can find out more information about experimental plot 9 and flog posts mentioning the experiment on the background page for the experiment.

As always, demo was a huge job this year. This season we added 3868 demo records and about 1539 survey records to our database. After over 20 years of this method, we are starting to get a very good idea of the demography of Echinacea in Solem Township.

So how do we do demo? When we find a new flowering Echinacea plant, we give it a tag and get its location with a survey-grade GPS (better than 6 cm precision). Then, we can revisit this plant for years to come and monitor its survival and reproduction. We’re monitoring over 10,000 plants as of 2018. With this many records, organizing demap in the future is going to be a big task!

We made some small adjustments to how we do total demo and flowering demo (we do flowering demo in every remnant now). Now, in our big plots, we only do a sample of the plants instead of total demo. Check out the updated table below (remember we did flowering demo everywhere). We still managed to shoot thousands of points, take even more demography records, and, as always, follow the colored flags!

| Total Demo |

BTG, Common Garden, DOG, East of Town Hall, KJs, Krusemark, Landfill West, Loeffler Corner East, Near Town Hall, Nessman, NNWLF, NRRX, recruit he, recruit hp, recruit hs, recruit el, recruit hw, recruit ke, recruit kw, RRX, RRXDC, South of Golf Course, Steven’s Approach, transplant plot, Tower, Town Hall, West of Aanenson, Woody’s |

| Sample Demo |

Aanenson, Around LF, East Riley, Hegg Lake, Elk Lake Road East, Golf Course, Landfill, Loeffler Corner, North of Golf Course, NWLF, On 27, Riley, Staffanson, Yellow Orchid Hill |

Evan and Will doing demo by the corn. While you might not be able to see the echinacea, we promise, it’s under there! Year started: 1996

Location: Roadsides, railroad rights of way, and nature preserves in and near Solem Township, Minnesota.

Overlaps with: Flowering phenology in remnants, fire and flowering at SPP

Data collected: demo records include Flowering status, number of rosettes, number of heads, neighbors within a 12 cm radius of plants found. These are all taken with PDAs that sync with an MS Access database. They are all transferred to the demap R repository in bitbucket with git version control.

GPS points shot: Points for each flowering plant this year shot mostly in SURV records, stored in surv.csv. Each location should be either associated with a loc from prior years or a point shot this year.

Products:

- Amy Dykstra’s dissertation included matrix projection modeling using demographic data

- Project “demap” merges phenological, spatial and demographic data for remnant plants

You can find out more about the demographic census in the remnants and links to previous posts regarding it on the background page for this experiment.

For her REU project, Brigid gathered data to study the relationship between flowering density and seed set. She worked at Staffanson Prairie Preserve, which appears to have higher flowering density in burn years than non-burn years. This year, 2018, was a burn year on the east side of the preserve. Brigid and Team Echinacea kept track of the style persistence of about ~150 individuals many of which we have phenology and style persistence information from prior years. These individuals were harvested and their achene count and seed set will be assessed by volunteers and interns at the CBG.

Brigid also observed nearest neighbors for many of the plants that she tracked. It might be the cases that echinacea flowers are more successful if they have other flowering plants nearby. Synchrony is a large part of why fire is so important, and, since SPP is our largest remnant prairie, it’s the best place to test the relationship between fire and synchrony. Number of heads, phenology, and head size may also \ interact with fire — we’ll know once we look at the data!

Site: Staffanson Prairie Preserve

Start year: 1996

Overlaps with: Phenology in Remnants, Reproductive Fitness in Remnants

Data and Samples: We shot 90 GPS points for nearest neighbors, many of which were plants that flowered for the first time this year. We also harvested 22 heads that are awaiting cleaning at CBG

Products: None so far

|

|