|

|

One of my projects this summer was monitoring the flowering phenology of Echinacea pallida in the restoration east and southeast of the parking lot at Hegg Lake Wildlife Management Area. When compared with Echinacea angustifolia flowering phenology, this will help us assess the temporal extent of the opportunity for hybridization between these species.

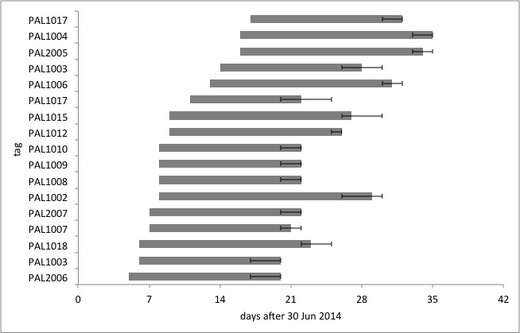

There were 19 flowering heads on 16 plants. The figure below illustrates the flowering periods of the 17 heads for which I could assess start and end dates (two heads finished flowering before I started monitoring). I define flowering period as the period from the first day of male florets to the last day of female florets. I estimated the last day of female florets based on patterns of flowering and style persistence. Error bars indicate the range of possible end dates (last day florets observed to first day no florets observed).

Nancy Braker and Marie Schaedel came to visit today! Nancy is the director of the Cowling Arboretum at Carleton College and Mary was a member of Team Echinacea 2013. They are also good friends of Jared’s and mine and prairie enthusiasts–so there was no disagreement about how we should spend our time.

We spent the day on a grand tour of three of the area’s largest and most diverse prairie remnants: Staffanson Prairie (right here in southwest Douglas County), Seven Sisters Prairie (near Ashby in Otter Tail County), and Strandness Prairie (Pope County). All are owned and managed by the Nature Conservancy. Every few steps we would find a new wildflower, grass, or insect to inspect, identify, and appreciate. It was a nice reminder of why we spend our days toiling in experimental plots and roadside ditches: to preserve the vibrant beauty of the healthy prairie.

Here are a few photos from our journey:

The sumac forest at Seven Sisters swallowed all but Jared’s binoculars.

In western Minnesota, a little elevation goes a long way (on top of Seven Sisters, 190 feet above Lake Christina).

Echinacea at Strandness Prairie. They look a little weird without flags and tags.

Prairie peeping makes for happy campers. (Strandness Prairie.)

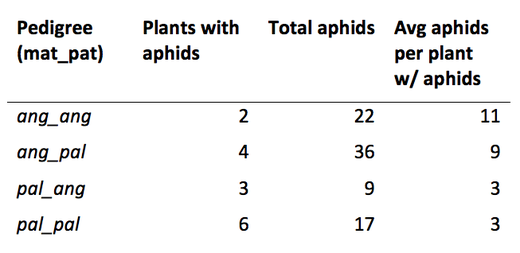

These are my preliminary results after adding 2 aphids to each of the 80 plants in my experiment (20 of each variant) and checking on their survival after about a week:

The most interesting result is that aphids were able to survive on each variant, including Echinacea pallida (“pal_pal”). Lauren Hobbs and Hillary Lyon found that aphids did not survive on E. pallida in their experiment. If the aphids persist, it could challenge the species’ status as specialist. If they eventually die off, it could provide an insight into what makes E. pallida inhospitable to them.

Another result is that, while E. pallida had the most plants sustaining aphids and E. angustifolia the least, E. angustifolia had the highest average aphid load and E. pallida the lowest. Perhaps it is harder for aphids to colonize E. angustifolia but easier for them to persist once present. It is important to note that the plants in this experiment are only a year old, and so perhaps aphid survival is more affected by plant size than pedigree at this stage.

I am continuing my additions and observations with extra gusto, because I can’t wait to see if these trends bear out over repeated trials, or whether new ones will emerge.

Studying aphids on Echinacea requires looking much more closely than I would otherwise. Sure enough, the closer I look the more I see. Here are just a few of my discoveries (namely the ones I’ve made since learning how to make my phone take macro photos):

I’m assessing survival of aphids on different Echinacea species and hybrids in P7, an experimental plot at Hegg Lake. I also checked for aphids on the non-native E. pallida growing in a nearby restoration. As I expected, I didn’t find any Aphis echinaceae, but I did find this much larger phloem-feeder.

A nearby E. angustifolia didn’t have Aphis echinaceae either, but it did have ants tending a flock of a different species of insect.

One week after the first aphid addition, two of the plants in my experiment had this little gray thing on them (but no aphids). It seems to be an exoskeleton. I wonder if it belonged to the aphids or something else?

Gretel and I found this winged adult surrounded by “white fuzzies” (the technical term we use in our records) on a plant in P1 today. The leaf they were on looked diseased, with lighter coloring overall and purple venation.

Finally, here are some ants tending a humongous herd of generalist aphids on a thistle. A dowry fit for any ant princess!

We spent the morning working on our personal projects. Elizabeth assessed style shriveling on her crossed flowers at Yellow Orchid Hill, where, she reports, flowering has recently passed its peak. Meanwhile, Claire and Jared performed crosses on the focal plants on the west unit of Staffanson. In P1, Will worked on his pollen preservation experiment and the Pollinator Posse (Keaton, Maureen, and Jennifer) surveyed P1 phenology. Further afield, Alli continued her flowering community analysis.

But the real action was at Hegg Lake, where I finished my first round of aphid additions to Echinacea angustifolia, E. pallida, and their hybrids in P7. I have almost doubled my efficiency since starting the additions, performing 20 additions in a little over an hour. I also surveyed the phenology of the 18 E. pallida flowering in the restoration nearby. Aphid survival and flowering phenology may seem pretty disparate topics–and they are–but they both inform our understanding of the consequences of introducing a non-native but closely related Echinacea species. Do they support the same aphids? How about their hybrids? How likely are they to hybridize? How much does their flowering phenology overlap? It’s hard to stick to just one question.

Doubtless inspired by my example, the rest of the team came to Hegg in the afternoon, where we measured plants in P2. Many of us we were able to increase our efficiency by working alone instead of in pairs, and row by row we progressed eastward. Less than an afternoon’s work remains.

Today was a big day for remnant phenology surveys–possibly our biggest of the season. We made the process more efficient by not recording style persistence on flowers on their 3rd, 6th, 7th, and 8th days of flowering.

But we didn’t stop there. We also collected pollen, painted bracts, and performed the first crosses with the 10 focal plants at Riley. Each focal plant was crossed with its nearest neighbor, its farthest neighbor within the remnant, the earliest flowering plant, and the latest flowering plant. This is to help us understand how compatibility varies across space and flowering time.

In other news, Will and I saw an immature bald eagle amongst the gulls and turkey vultures at the landfill.

Here is the latest draft of my proposal to investigate the survival rates of Aphis echinaceae on Echinacea hybrids and the impact they have on host fitness:

CMS_proposal_8Jul2014.pdf

I’m excited to get started. In addition to my main project, I will be conducting and coordinating a variety of side projects related to aphids and Echinacea hybrids:

1. Katherine Muller and Lydia English’s aphid addition/exclusion experiment in P1.

2. Assessing fitness of the two Echinacea species and their hybrids in P6 (Josh’s Garden) and P7 (at Hegg Lake).

3. Recording flowering phenology of Echinacea pallida at Hegg Lake, where they were planted in a prairie restoration.

Having mutually pledged to the Echinacea Project our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor, we set out this fine Saturday morning to survey the flowering phenology of Echinacea in the prairie remnants. We are interested in phenology (the study of recurring phenomena) because just as distance can genetically isolate fragmented populations, so can time. Since Echinacea cannot reproduce with itself, it needs to be flowering at the same time as a compatible mate if it wants a chance to reproduce.

To quantify flowering phenology, we have to check on the flowers every few days. Echinacea is just beginning to flower now, and we don’t want to miss anything. Today we split up into two-person teams, went to different remnants, and recorded the progress of every flowering Echinacea. All our work locating and flagging plants earlier this week allowed us to move efficiently through the sites, finishing our survey by mid-day. Here we are converging at the final site:

A formidable crew undertaking a daunting task in pursuit of a noble goal: what a glorious Saturday!

We started out the day doing what we do best: searching for seedlings in Experimental Plot 8 (a.k.a. Q2). Having braved formidable winds to plant them late last October, Stuart, Gretel, and Ruth were visibly relieved to see them pop up this spring. Since last week Team Echinacea has been diligently tracking down each seedling and “naming” them with colored toothpicks and row location coordinates, accurate to one centimeter.

In the afternoon we located and counted Echinacea in the recruitment experiment, a continuation of the project described in this paper. The procedure is really fun: we find the boundaries of the plots with metal detectors, triangulate points, then search within an area exactly the size of a regulation 175-gram Disc-craft Ultra Star disc (a.k.a. frisbee). Go CUT!

The best part of the day was tagging my first Echinacea. Maybe it just lost its old tag, but I like to think this is the first time this plant has ever born the silver badge. Sometime 10-12 years ago, this seed was planted. Now that it is finally about to flower, it has the honor of going down in history in the databases of the Echinacea Project, living out the rest of its life in the service of science. This 23rd of June, 3.65 m from the southwest corner and 0.79 m from the southeast corner of the northeast plot in Recruit 9, I named a flowerstalk “19061.” Isn’t it beautiful?

Doesn’t the flower head look ripe? Stuart says we may start to see flowering as early as the end of this week!

Eventually the time came to leave my new friend and join the rest of the team. This is where they were:

(Can you spot the team?)

A nice day is Douglas County is a very nice day.

My name is Cam Shorb, and I’m a junior Biology major at Carleton College. Click here for more about me and my summer research interests.

|

|