Hi Flog! I am at ESA this week presenting results from my Master’s Thesis work on solitary, ground-nesting bees. Check out my poster below!

Check out this link for more updates on this experiment.

|

||||

|

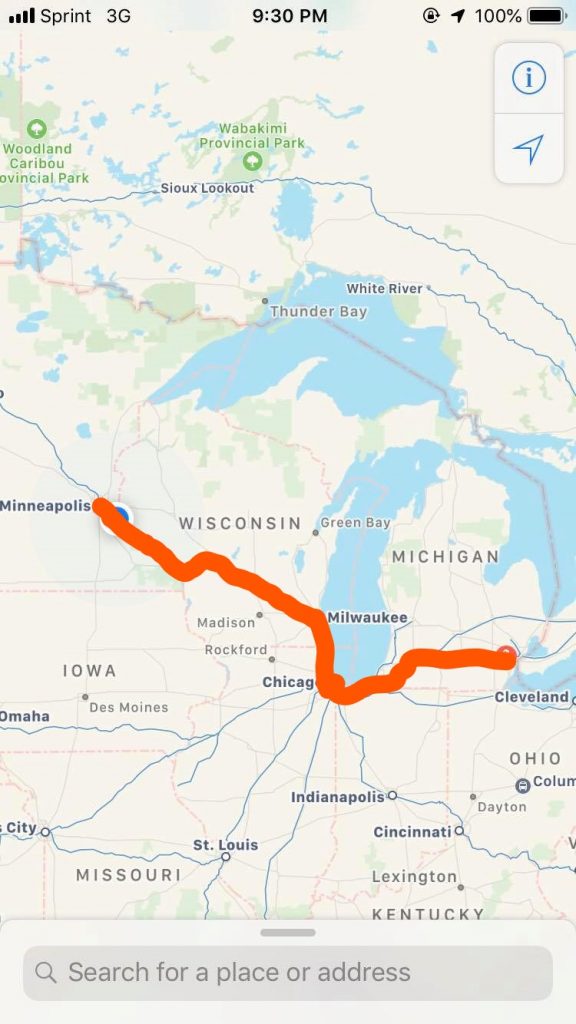

Hi Flog! I am at ESA this week presenting results from my Master’s Thesis work on solitary, ground-nesting bees. Check out my poster below! Check out this link for more updates on this experiment. Hello, flog followers! This is going to be a joint flog post for Sunday and Monday (mostly Sunday…). Sunday was a travel day for me. I woke up at 5:30 am and hopped on the Amtrak train in Dearborn, Michigan and headed back to Chicago, Illinois.  While on the train I worked on revisions for my Master’s thesis and worked on a poem while I drank my coffee.  When I arrived in Chicago, I had two hours to kill before my next train. So, I grabbed lunch at Chipotle and hung out in the main hall of Chicago’s Union Station.   While on the train from Chicago to Minneapolis, Minnesota I worked on my Master’s thesis some more.   When I arrived in Minneapolis I had to take the Green Line to Stuart’s brother’s house. This is where I left my car while I was out of town. So, here is a thank you to him and his family for that!  There went my remaining woes I am so thankful Finally arrived in Kensington, Minnesota around 1:15 am and in bed by 2 am.  Woke up Monday and got to work with Team Echinacea after my week away! We went out to Experimental Plot 2 and took phenology data and administered our pulse/steady pollination treatments.  After work in P2 I went out to Riley and collected seeds. Saturday started with the three present townhallers (Erin, Julie, and myself) heading out to the field with John and Stuart in order to collect phenology data from one of our experimental plots. Jay and Riley decided to take a trip back to their undergrad institute for the weekend and Shea had prior commitments too.   Erin and I stumbled upon a mutant floret on an Echinacea. Typically the ray florets (the long pink ones people usually think of as petals) are sterile and have unforked stigma but this one has a forked stigma! Question is it receptive to pollen?  Once we finished up our phenology data collection we headed back to town hall to relax. However, I decided to take a trip out to Staffanson to work on some poems and found that someone had driven through the remnant prairie!  I have no idea who did this or why but it made me fairly disappointed. Nevertheless, I had a productive afternoon in Staffanson. Hi all! If your looking for a report on planting at WCA (and you have access to the dropbox), here’s where you can find all the necessary files: \Dropbox\CGData\185_germinate\germinate2019 \Dropbox\CGData\195_plant\plant2019 \Dropbox\geospatialDataBackup2019\planting2019 Additionally, you can read the full report here: \Dropbox\CGData\195_plant\plant2019\plantingReport.docx Have fun! Michael Hello flog! If you’ve been reading carefully, you’ll remember that we planted some seedlings here (at Echinacea Team “West” I guess) about a month and a half ago. Now, those seedlings are growing some big ol’ true leaves, and are almost ready to go in the ground! We have ~1400 seedlings to plant in Minnesota, and more will be coming for College of Wooster. I’m currently working on putting together the master plan for putting these all in the ground. Watch out for a flog about that, because its going to be one busy, dirty day digging in the prairie

In 2018, we collected data on the timing of flowering in 333 individual plants growing in our naturally occurring prairie remnants: 119 plants at Staffanson Preserve and 214 at others remnants. Flowering began on June 20th – four days earlier than last year. The last date of flowering was on August 9th – the latest bloomer was a roadside plant that had been mowed early in the season but put up another stem later in the season. Peak flowering for the remnants we observed in 2018 was on July 9th, which again was 4 days earlier than 2017. That day there were 257 individuals flowering. The figure below was generated with R package mateable, which was was developed by Team Echinacea to visualize and analyze phenology data. From 2014-2016, determining flowering phenology was a major focus of the summer fieldwork, with Team Echinacea tracking phenology in all plants in all of our remnant populations. Stuart began studying phenology in remnant populations in 1996, but he didn’t know that keeping track of the dates was called “phenology.” In following years, several students & interns also studied phenology in certain populations. The motivation behind this study is to understand how timing of flowering affects the reproductive opportunities and fitness of individuals in natural populations. Start year: 1996 Location: roadsides, railroad rights of way, and nature preserves in and near Solem Township, MN Overlaps with: Phenology in experimental plots, demography in the remnants, reproductive fitness in remnants Physical specimens:

Data collected: We identify each plant with a numbered tag affixed to the base and give each head a colored twist tie, so that each head has a unique tag/twist-tie combination, or “head ID”, under which we store all phenology data. We monitor the flowering status of all flowering plants in the remnants, visiting at least once every three days (usually every two days) until all heads were done flowering to obtain start and end dates of flowering. We managed the data in the R project ‘aiisummer2018′ and will add it to the database of previous years’ remnant phenology records. Ask Amy Waananen for more specific data regarding phenology in the 2017 and 2018 seasons. GPS points shot: We shot GPS points at all of the plants we monitored. The locations of plants this year will be aligned with previously recorded locations, and each will be given a unique identifier (‘AKA’). We will link this year’s phenology and survey records via the headID to AKA table. Ask Amy Waananen for more specific data regarding phenology in the 2017 and 2018 seasons. You can find more information about phenology in the remnants and links to previous flog posts regarding this experiment at the background page for the experiment.  A pallida head. Notice the white pollen, which is the only 100% sure way you can be sure a head is pallida and not angustifolia Echinacea pallida is an Echinacea species that is not native to Minnesota, but instead ranges East of the range of E angustifolia (and SE of our research site). In the summer of 2018, we identified 96 flowering E. pallida plants with over 200 heads that were planted in a restoration at Hegg Lake WMA. Every year for the past several years, we have visited the E. pallida plants, taken phenology data, and chopped off their heads. We do this to prevent E. pallida from being a bad pollen source or sink for native E. angustifolia populations. We were able to do this early this year, as E. pallida flowers significantly earlier than E. angustifolia. We went back to check if we missed any heads on in September and found 3. They were done flowering, but hadn’t dropped seeds. We collected those heads, and they are currently stored at CBG. We hope that we might be able to germinate them for tissue. We want to analyze the ploidy of pallida compared to angustifolia. We have sneaking suspicions that pallida may be tetraploid where angustifolia is diploid. Start year: 2011 Location: Hegg Lake Wildlife Management Area restoration Overlaps with: Echinacea hybrids (exPt6, exPt7, exPt9), flowering phenology in remnants Physical specimens: 200+ heads were cut from E. pallida plants and removed then composted. We brought three heads back with us to Chicago Botanic Garden. Data collected: All pallida data is in demap GPS points shot: We shot points for all flowering E. pallida plants. Products: In Fall 2013, Aaron and Grace, externs from Carleton College, investigated hybridization potential by analyzing the phenology and seed set of Echinacea pallida and neighboring Echinacea angustifolia that Dayvis collected in summer 2013. They wrote a report of their study. Pallida counts are being somewhat incorporated into demap. Previous team members who have worked on this project include: Nicholas Goldsmith (2011), Shona Sanford-Long (2012), Dayvis Blasini (2013), and Cam Shorb (2014) You can find more information about Echinacea pallida flowering phenology and links to previous flog posts regarding this experiment at the background page for the experiment. The tallgrass prairie once occupied vast expanses of land across America’s heartland. Today, it is among the most threatened and least protected habitats in the world. Each year, parts of the tallgrass prairie continue to be lost to agriculture and development making the conservation and protection of this system of utmost importance. Native bees are the most abundant and most important pollinators in the tallgrass prairie. The bees that we study for this project are called solitary bees. They are different from honeybees in that they are native to North America. They are also different from bumblebees (where many genera are native to North America) in that they do not form a colony and build their nests individually. We know a lot about the kinds of things bees like to eat (pollen and nectar) and their foraging behavior. However, most solitary bees spend the majority of their life in their nests, yet we know so little about what conditions are suitable for them to build their nests. In the tallgrass prairie, over 80% of bees are solitary, ground-nesting bees. We have a lot to learn about the kinds of habitat suitable for them to build their nests in. We know some things about what ground-nesting bees may like. Evidence suggests they might like sandy soil, bare ground, and well-drained, south-facing slopes. However, we don’t know what bees in the tallgrass prairie may like for their nesting habitat conditions as most of these studies have been done across other ecosystems. Much of the prairie has been changed from its original condition. We call the history of this condition “land-use history.” I am interested in how the history of the land may determine where bees build their nests in the ground. Some common types of land use history are remnant prairies which are pristine habitats with untilled soil, prairie restorations which are plantings of prairie plants with disturbed soil, and old fields which are fields leftover from agriculture that may have been tilled or grazed. Using emergence traps, we moved traps everyday for a total of 1,440 across the season. We caught 110 ground-nesting bees in traps across 24 sites this summer. I placed traps at 8 different locations, each with three different land types at each location (remnant prairie, prairie restoration, and old fields). We found that the most bees nest in the prairie (40), while restorations and old fields have the same numbers of nesters (35). While land use is not good at determining bee nests, we did find that the location and land use when combined are both important in determining where bees nests. I also placed pan traps at all 24 sites and caught 564 bees. Pan traps were colored blue, white, and yellow to attract a diversity of foraging bees at every site. We will use these bees to compare the foraging and nesting communities at each site. I also measured many microhabitat characteristics of the soil and vegetation at some of the traps. We found that bare ground is a good predictor of where bees build their nests. We also found that the soil texture, especially the amount of silt and sand help determine where bees nest. A diverse plant community with lots of native plants is also a good predictor for bee nests. We still have a lot more work to do to determine where bees are building their nests. Our next steps are to identify all the bee specimens caught in ground nests and in pan traps. Once specimens are identified, we can learn more about the species specific results for ground nesting bees. Start year: 2018 Location: Hegg Lake Wildlife Management Area restoration, Riley, Aanenson, East Elk Lake Road, and other non-project sites Overlaps with: Pollinators on Roadsides Physical specimens: 674 bees were brought back to CGB and are currently being pinned and photographed by Mike Humphrey. Soil samples were collected from every location where bees were caught + a random sample from other traps. GPS points shot: We shot points for all trap locations. Ask/email Kristen for this data. Products: This work is part of Kristen’s Master’s thesis Previous team members who have worked on this project include: Anna Vold (2018) Thanks so much to help from Team Echinacea 2018, especially Anna Vold who helped measure soil texture. Also many thanks to Emily Staufer from Lake Forest College who processed bees from HFW, and Mike Humphrey who has pinned some bees from this project. Finally, I get to show all of you my poster! Like Tris, I am also presenting work related to pollen limitation in Echinacea. For my project, I simply tried to find whether pollen limitation is present in Echinacea or not. What I found – it’s not (though, after presenting this poster, there has been some controversy!). It just seems that echinacea produces as much seed as it can up to a certain limit, then stops, regardless of whether more styles were pollinated. I went a little unorthodox with the way I designed this poster. Instead of the normal “wall of text” design, I instead opted to use the “better poster” design created by Mike Morrison. I really liked using this! It was so incredibly easy to make, and it really facilitated great conversations with everyone who stopped by poster slot #37. I’m very much looking forward to using this poster design each and every time I present from now on. Title: No evidence of pollen limitation in the long-lived perennial Echinacea angustifolia Presented at: MEEC 2019 at Indiana State University in Terre Haute, IN When: April 27th, 2019 Poster Link: MCL Pollen Limitation MEEC Poster Welcome back to the next installment on this series of planting seeds for our new experimental plot. If you remember from the last post, I posed the question – do you think that this second planting would have more or fewer seeds than the last one? More. It was more. While we planted 800 seeds on Wednesday, on Friday we planted a good 1400 seeds. As you can imagine, this took considerably more time. But luckily, we had even more help! Anne and Priti both came to help with planting. Anne even came up with an ingenious way to use toothpicks to track which head each seed in a plug came from. Now, we have 2200 planted seeds! Seeing as our original goal was 1200 – I’d say that’s not to shabby. Cotyledons are starting to burst through in our farthest ahead seedling and they are all chugging along at a steady pace. Personally, I love watching these little guys grow and get a lot of satisfaction from knowing that they will grow up to flower some day and be used in experiments for many years to come. That being said, it’s really going to be a monumentous effort to plant all of these guys. Hopefully team echinacea 2019 will be up to the task. Oh yeah, be on the lookout for bios from Team Echinacea 2019 coming soon! |

||||

|

© 2024 The Echinacea Project - All Rights Reserved - Log in Powered by WordPress & Atahualpa |

||||