We started off today assessing phenology in all of the remnants, and both experimental plots. I went to p2 with Anna and Ashley where we saw all stages of flowering from bud to done! One of the Echinacea plants I visited in p2 was gone, pulled down into a gopher mound. But many more plants were flowering and pollinators were busy collecting pollen. We met back at the Hjelm house for lunch, and had a nice meal on the porch. Our lunchtime conversation turned to one where we discussed the importance of telling a good narrative in science. We learned all about the “ABT” structure which consists of connecting two known facts with “and”, revealing the gap in understanding with, “but”, and finishing off with a “therefore” statement which offers resolution. The “ABT” format is useful for clarifying and communicating ideas, but it isn’t easy to do well right away, so we practiced framing our research projects in the ABT format- a good exercise for everyone! Next up we split into teams, worked on projects, added aphids the aphid addition plants in p1, finished mapping the Echinacea pallida plants at Hegg Lake, and wrapped up the day.

|

||||

|

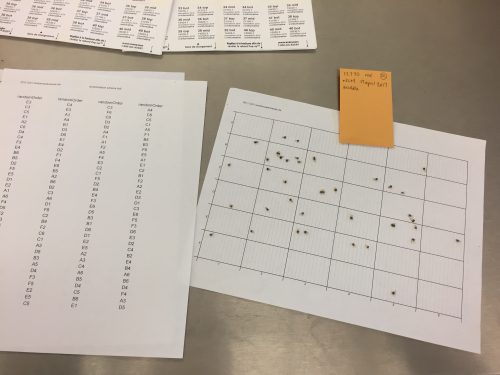

Today we had a slightly late start because we were concerned about weather. But, the rain held out and we managed to have a productive day! Ashley, Anna, Alex and I started the day with phenology and searching for Echinacea at Aanansen. This remnant is particularly interesting this year because many trees were removed from the top of the hill, making the landscape look totally different! After lunch, I went around solo for a bit and worked on vegetation analysis at some of my roadside sites. I’ll explain the project in more detail in a future flog post, so stay tuned! Finally, we ended the day by identifying all of the flowering Echinacea up at p2. After work, the Andes crew headed in to Alexandria to do some errands and try Culver’s (many of us for the first time!)  Sunset at Andes! Team Echinacea had a busy Saturday doing various things. I drove back from St. Paul, MN. I was there for a friends birthday. Wes saved the St. Olaf band camp with the magic of his tuba. Other members of the team did laundry in Alexandria and went out to eat at Mi Mexico (conveniently located 50 meters from the laundromat). Some members did actual work also! Lea found the locations where yellow pan traps, which are used to sample pollinators, were placed in 2004. She plans to use these sites along with some others for her study on community composition along roadsides. Alex is also going to be using those locations to put out yellow pan traps again this summer, he plans to compare pollinators caught this summer to those caught in 2004. Will Howdy Flog Followers, After the scanning is completed and all of the achenes have been counted, the next process is randomizing. Randomizing consists of taking the top, middle, and bottom sections of achenes and separating their achenes into an informative and uninformative subcategory. The goal of this step is to get a random, and therefore representative, sample of achenes from the middle. For the informative subcategory, the goal is to place 30 achenes from the top, middle, and bottom section into clear envelopes. The top and bottom achene sections normally have 30 achenes already within their section, due to the extraction method used that aimed to get 30 achenes from the top and bottom before moving on to the middle. So, in exchange the middle section of achenes normally has a larger number of achenes. In order to narrow the large sections of achenes down to 30, randomization is necessary. Steps for randomizing:

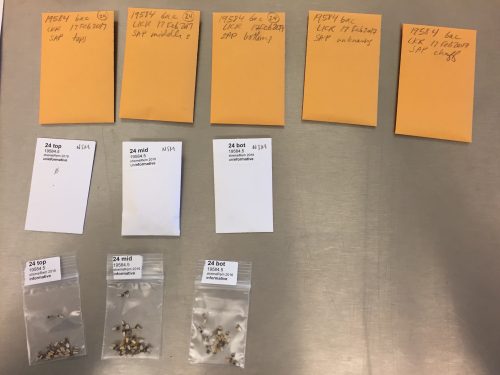

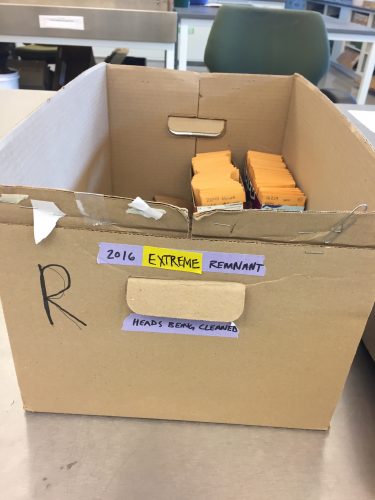

All of the remaining achenes from randomization that were not chosen are put into the uninformative subcategory. Ray achenes, achenes with holes, and achenes that have been crushed along the way are considered uninformative. These are placed in small white paper envelopes. After the achenes are separated into their informative and uninformative subcategories, they must be labeled with their corresponding sticker. This is so that their identification, and therefore the extreme quality that the seed-head possesses, is not lost.

Seen in the image directly below is The Final Product: 11 envelopes. 3 of these envelopes are the clear bags full of the informative achenes, from the top, middle, and bottom sections, that will move on to be X-rayed. The use of clear bags is for X-ray purposes, so that a clear shot of the achenes is achieved.

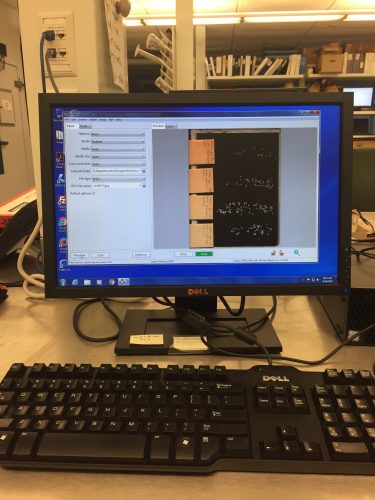

‘Till next time folks, Nicolette McManus Howdy Flog Followers, After cleaning a whole bunch of seed-heads, I began the process of scanning. Scanning is a rather simple process. Out of the 5 achene envelopes for each seed-head, the four envelopes containing achenes (excluding the chaff) are used. Each section is poured out onto a glass ‘sheet’, that is placed onto the scanner. I loaded each section with its corresponding label from the paper envelope, for identification and to avoid confusion between the different sections. In the image below, from the bottom to the top of the glass sheet the achene sections : top, middle, bottom, other. The middle section is the most noticeable, as it normally has the largest number of achenes. After all the achenes are placed onto the glass sheet, a cover is placed over the sheet, for the sake of darkness. Then the scanning can commence! Each resulting scan looks similar to the second image, on the computer screen. Lastly, it is important to have a specific place to save all of the scans to. I have saved all of the extreme scans to the ‘EchinaceaCG2016’ Folder, under the I Drive. This way, everyone (including yourself) will be able to find your hard work.

The scanned images are then used to count all of the seeds found on that specific seed-head. Specifically, the seeds are counted in reference to their category (top, middle, bottom, or other), which can be combined for a total count value. As a result, we are able to compare the sizes of the seed-heads, based on achene count. ‘Till next time folks, Nicolette McManus Today was Amy Waananen’s last day working at the Chicago Botanic Garden with the Echinacea Project. The last few days were a flurry of activity with our potluck, preparing for prescribed burning in Minnesota, and getting ready for the summer field season. On top of that, Amy submitted a manuscript about reproductive synchrony to The American Naturalist. It’s sad to see Amy leave but we’re happy that she will be nearby. She is working out on the prairie in western Minnesota the summer with her new lab group. It is great she is starting a PhD program at the University of Minnesota this fall. Good luck, Amy! Howdy Flog Followers, I spent the past two weeks diving into the initial process for the ‘Extremes Project’: cleaning as many seed-heads as I can get my hands on. I’m sure that all of you seasoned flog followers are familiar with this process. To clarify, cleaning a seed-head consists of extracting all of the achenes. An achene is a white ‘case’ that contains the seeds (seen under the magnifying glass in the photo below). There is a range of 50 – 400 achenes found in a single seed-head. However, specifically for the extremes project, it is important to extract the achenes based off of their location on the seed-head: top, middle, and bottom. Top, Middle, Bottom, Other, Chaff. There are five separate envelopes that need to be filled for the Extreme extractions. I have been able to develop a method of satisfying all the categories as precisely as possible. First, I start by extracting a minimum of 30 achenes from the top, followed by at least 30 achenes from the bottom. However, the bottom is tricky because of the sterile ‘ray achenes’ found along the bottom edge of the seed-head. These ray achenes, along with unknown / runaway achenes are placed into the ‘Other; category. Then, all of the remaining achenes on the seed-head are put into the ‘Middle’ category. Lastly, all of the chaff, the leftover ‘flower guts’, is collected into its own category envelope. The small seed-heads that I have encountered require an even more delicate approach than the others. This is based on the fact that they do not have a full 30 top nor full 30 bottom achenes that could be extracted individually. So, as a compromise, I would extract five achenes from the top and then five achenes from the bottom. While alternating, I would continue until I had a maximized amount of equal top and bottom achenes. It has been an interesting experience working with the Extreme seed-heads. I have found lots of variation in the Extreme seed-heads. For instance, there is a great difference in sizes between all of the seed-heads. There was even a seed-head that did not have any achenes, zero. Additionally, there are more frequent occurrences of running into dead larvae and cat frass (caterpillar poop, that looks like a spiderweb-like structure) on the heads, which keeps things interesting. Now, on to the next step: Scanning! This step allows for me to be able to count all of the seeds in all of the categories while also documenting everything digitally. Tune in next week for more details on Scanning. The flowers on these heads bloom from the bottom to the top. We can use this information to gather at what point the flower was being fertilized by pollinators. For example, if only the bottom achenes are fertilized, then that tells us that the particular seed-head was an early-bloomer or was fertilized early in it’s blooming process. This is the reason why it is important to isolate the top, middle, and bottom achenes. Plus, isolating the achenes into these categories allows for data comparisons and individual interpretations down the road. By the end of my analysis, I hope to use the data that I have collected to help the echinacea team find positive fertilization patterns for this plant, in order to help to conserve their populations.

‘Till next time!! Nicolette McManus Aphis echinaceae is a specialist aphid that is found only on Echinacea angustifolia. It feeds on sap in Echinacea leaves, and can also be found on flowering heads. This aphid also attracts “ant bodyguards”, which protect the aphids from predation, and in the process may also fend off other potential herbivores. Prior studies by Team Echinacea members have demonstrated that aphid presence does not lead to significant changes in plant fitness in observational studies, although in controlled experiments aphid presence does affect herbivore damage. Furthermore, inbred plants are more susceptible to aphid presence than outbred plants. In 2011, Katherine Muller designated a sample of 100 plants in experimental plot 1 for aphid addition or removal. The presence or absence of these aphids is maintained by team members two to three times per week. In summer 2016, aphid levels were assessed and maintained 14 times on 70 of these plants (addition on 33, exclusion on 37) from early July until early August. In September, Amy Waananen recorded signs of senescence in the leaves of treatment plants. This data can be combined with data from our common garden measuring data to explore the richness of the Echinacea-aphid relationship. Start year: 2011 Location: Experimental Plot 1 Overlaps with: Phenology and fitness in P1 Data collected:

Products:

You can read more about the aphid addition and exclusion experiment, as well as links to prior flog entries mentioning the experiment, on the background page for this experiment. Hello all you flog followers, My name is Nicolette and I am a new student intern for The Echinacea Project team! I would like to introduce myself, as I will be posting along the way of my Echinacea journey. I am currently a sophomore at Northwestern University studying Environmental Science and Art Theory & Practice. I am super excited to be a part of a specific project here and I am intrigued to see the results! I will be working on the “Extremes Project”. Essentially, this project will reveal the variations of seed fertilization among the ‘”extreme” plants. When I use the word “extreme”, I am referring to the echinacea plants who bloom earliest, latest, or are located at far distances away from other clusters of echinacea plants. We hope to use the data we collect in order to make sense of these patterns and further be able to help conserve this native prairie species.

I will begin extracting achenes from these “extreme” seed-heads today, and will keep you updated with the process and discoveries! ‘Till next time folks, Nicolette McManus

Hey Flog readers, Sam here. After a quarter of hard work, all of the achenes from my thirty-two flowerheads have been counted, x-rayed, and classified! I am looking forward to analyzing the data next quarter in R through a class Stuart teaches at Northwestern. It’s been quite a journey learning about both the nitty-gritty of going from flower head to data sheet and the conservation biology through which we contextualize our data. Special thanks to Stuart for giving me the opportunity to intern for the Echinacea project, to Amy and Scott for being wonderful, helpful mentors, and to everyone else in the lab for your amazing company and support. If anyone reading this would like to know more about what it is like to intern for the Echinacea Project, feel free to e-mail me at Samuelhamilton2017@u.northwestern.edu. Best, |

||||

|

© 2024 The Echinacea Project - All Rights Reserved - Log in Powered by WordPress & Atahualpa |

||||