|

|

Successful pollination leads to full achenes and higher fitness later in the season! This summer we counted shriveled and non-shriveled rows of styles three times per week for every Echinacea head in 8 of the 28 remnant populations. We also harvested 121 Echinacea heads to be analyzed for seedset data. This year we selected heads for harvest based on their position within randomly selected plots where Tracie Hayes and Lea Richardson collected vegetation data. In every randomly selected vegetation plot, all species were identified and we recorded their abundance. We marked any Echinacea head within a vegetation plot for harvest. Harvested heads are ready to be processed by citizen scientists at the Chicago Botanic Garden. In the lab, heads will be cleaned so that all achenes can be counted and x-rayed to determine seedset.

Measuring the reproductive success of an Echinacea angustifolia head gives insight into the fitness of the individual. In remnant populations, we measure reproductive success using two methods: style persistence and seedset. Seedset is the proportion of all seeds that are viable in an Echinacea head, and is measured in the lab after heads have been harvested. Style persistence is a fitness measure that can be taken during the field season. Styles, the showy female reproductive structures that emerge from every floret in an Echinacea head, shrivel within 24 hours if they receive compatible pollen. Keeping track of how many styles shrivel and how many persist can give us a sense of the reproductive success of that head without any lab work.

Year: 1996

Location: Roadsides, railroads and rights of way, and nature preserves in and near Solem Township, Minnesota.

Overlaps with: flowering phenology in remnants, mating compatability in remnants

Physical specimens: 121 harvested heads, currently at the Chicago Botanic Garden

Data collected:

- Style persistence data for each flowering head, collected three times per week, stored in remData

- Dates and identities of harvested heads, stored on paper datasheets entered electronically into richHood

GPS Points Shot: A point for each flowering head, stored under PHEN and SURV records in GeospatialDataBackup

Products:

You can find out more about reproductive fitness in the remnants and read previous flog posts about it on the background page for the experiment.

Echinacea head with pollinator exclusion bag. Does receiving the maximum amount of pollination vs. no pollen at all affect a plant’s longevity or likelihood of flowering in subsequent years? We are trying to find out in this long-term experiment, but flowering rates have been so low in the past few years we are not learning much.

This summer, only three plants flowered of the 27 plants remaining in the pollen addition and exclusion experiment. We continued experimental treatments on these flowering plants and recorded fitness characteristics of all plants in the experiment. Of the original 38 plants in this experiment, 13 of the exclusion plants and 14 of the pollen addition plants are still alive.

In this experiment we assess the long-term effects of pollen addition and exclusion on plant fitness. In 2012 and 2013 we identified flowering E. angustifolia plants in experimental plot 1 and randomly assigned one of two treatments to each: pollen addition or pollen exclusion. When plants flower in subsequent years they receive the same treatment they were originally assigned. Because flowering rates have been so low in 2016 & 2017, differences in flowering due to treatment are not detectable.

Start year: 2012

Location: Experimental plot 1

Physical specimens: We harvested three flowering heads from this experiment that will be processed with the rest of the experimental plot 1 heads to determine achene count and proportion of full achenes.

Data collected: We recorded data electronically as part of the overall assessment of plant fitness in experimental plot 1. We recorded dates of bagging heads and pollen addition on paper datasheets.

You can find more information about the pollen addition and exclusion experiment and links to previous flog posts regarding this experiment at the background page for the experiment.

Aphids on an Echinacea leaf This summer Team Echinacea continued adding and excluding aphids to plants in the experiment that Katherine Muller started. In 2011, Katherine Muller designated a sample of 100 Echinacea plants in experimental plot 1 for aphid addition or removal. The presence or absence of these aphids was maintained by team members once a week in the summer of 2017, for a total of 7 weeks from early July to mid August. We maintained addition on 31 plants and exclusion on 30, for a total of 61 plants. Will Reed set up a data entry system where we could enter data twice from the paper sheets and check for data-entry errors. In early October, Lea Richardson and Tracie Hayes recorded signs of senescence in the leaves of treatment plants. This data can be combined with data from our common garden measuring data to explore the richness of the Echinacea-aphid relationship.

Aphis echinaceae is a specialist aphid that is found only on Echinacea angustifolia. Read more about this experiment.

Start year: 2011

Location: Experimental Plot 1

Overlaps with: Phenology and fitness in P1

Data collected:

- Aphid counts for each treatment plant on each observation day, on paper

- Aphid counts recorded in csvs, on the teamEchinacea2017 dropbox

- Leaf senescence data, recorded on paper

- Initial and final assessment of aphid counts on treatment plants, recorded on paper

- Aphid counts also included in p1 measuring data

Products:

- 2016 paper by Katherine Muller and Stuart on aphids and foliar herbivory damage on Echinacea

- 2015 paper by Ruth Shaw and Stuart on fitness and demographic consequences of aphid loads

- 2015 poster by Daniel Brown and Kyle Silverhus (Lake Forest College) on achene and seed set differences on treatment plants

You can read more about the aphid addition and exclusion experiment, as well as links to prior flog entries mentioning the experiment, on the background page for this experiment.

This year we monitored the original 28 C. hillii rosettes at Hegg Lake WMA to check the fitness and persistence of our original individuals/population. Presently, 10/28 rosettes remain, all as non-flowering basal rosettes. For each rosette, we measured the length of the longest axis and the corresponding perpendicular axis. No burns were conducted this year.

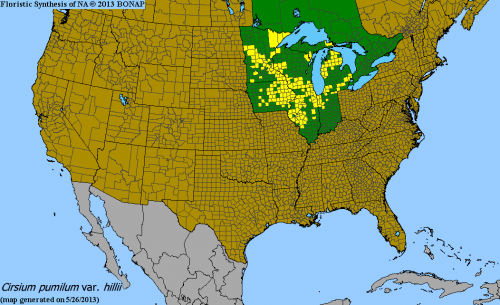

This experiment assesses effects of fire on the fitness of Cirsium hillii (Hill’s thistle) plants at Hegg Lake WMA. Like Echinacea, C. hillii inhabits dry prairies, but Hill’s thistle is listed as a Species of Special Concern in Minnesota and little is known about how it responds to fire. Burn and non-burn units were created prior to an experimental fall burn conducted by the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) in 2014. That year, we mapped 28 C. hillii rosettes (basal and flowering).

The distribution of Cirsium hillii, a rare endemic to the Great Lakes region. Last year was also a non-burn year, although of rosettes found, there were three flowering rosettes. It’s challenging to determine cases of mortality with this species, since C. hillii is clonal, and it’s possible that each rosette is not a unique individual.

In 2015, Abbey White found that there was only one or two individuals in our C. hillii “population!” We don’t know of any other C. hillii populations in Douglas County. We are possibly monitoring the last individual in the area.

You can find out more about Cirsium hillii fire & fitness and read previous flog posts about it on the experiment background page.

We observed that 95% surviving members of the 1996 cohort were basal in 2016 Does receiving the maximum amount of pollination vs. no pollen at all affect a plant’s longevity or likelihood of flowering in subsequent years? In this experiment we assess the long-term effects of pollen addition and exclusion on plant fitness. In 2012 and 2013 we identified flowering E. angustifolia plants in experimental plot 1 and randomly assigned one of two treatments to each: pollen addition or pollen exclusion. When plants flower in subsequent years they receive the same treatment they were originally assigned.

Across all experiments, 2016 was a low flowering year. Only four plants flowered of the 29 plants remaining in the pollen addition and exclusion experiment. We continued experimental treatments on these plants and recorded fitness characteristics.

Start year: 2012

Location: Experimental plot 1

Physical specimens: We harvested four flowering heads from this experiment that will be processed with the rest of the experimental plot 1 heads to determine achene count and proportion of full achenes. The labels for these heads, beginning with the letter “p,” identify them as part of the pollen addition and exclusion experiment.

Data collected: We recorded data electronically as part of the overall assessment of plant fitness in experimental plot 1. We recorded dates of bagging heads and pollen addition on paper datasheets.

You can find more information about the pollen addition and exclusion experiment and links to previous flog posts regarding this experiment at the background page for the experiment.

E. pallida heads are easily distinguished from E. angustifolia by their white pollen and longer ray florets. Echinacea pallida, an Echinacea species compatible with E. angustifolia, but not native to our study area, was planted at a restoration at Hegg Lake WMA. One trait of E. pallida may limit its potential to hybridize with E. angustifolia individuals is the synchrony of their flowering timing, or phenology. To study this, we have kept track of the start and end dates of flowering for Echinacea pallida individuals in the Hegg restoration plot since 2011. In 2016, we identified 66 flowering plants with 113 heads. Flowering began on June 18th. Then, around July 7th, we chopped off all the Echinacea pallida heads.

Start year: 2011

Location: Hegg Lake WMA restoration

Overlaps with: Echinacea hybrids (exPt6, exPt7, exPt9), flowering phenology in remnants

Physical specimens: 113 heads were cut from E. pallida plants circa 7 July 2016 (the last day of recorded phenology). These specimens were likely composted.

Data collected: We collected phenology data using handheld computers.

GPS points shot: We shot points for the 66 flowering E. pallida plants.

Products: In Fall 2013, Aaron and Grace, externs from Carleton College, investigated hybridization potential by analyzing the phenology and seed set of Echinacea pallida and neighboring Echinacea angustifolia that Dayvis collected in summer 2013. They wrote a report of their study.

Previous team members who have worked on this project include: Nicholas Goldsmith (2011), Shona Sanford-Long (2012), Dayvis Blasini (2013), and Cam Shorb(2014)

You can find more information about Echinacea pallida flowering phenology and links to previous flog posts regarding this experiment at the background page for the experiment.

The team after an initial measurement of p9. Blue flags are positions where Echinacea weren’t found. This summer, we remeasured plants in experimental plot 9 at Hegg Lake. These plants are hybrids of Echinacea angustifolia (native) and Echinacea pallida (non-native, but planted at a nearby restoration). Unlike the plants in p7, these plants came from open-pollinated parents – that is, there was no artificial crossing done. Stuart and Lydia English planted the seeds in May of 2014. Much like with plot p7, an analysis the survival and fitness of these plants can give insight into whether or not hybrid populations can be viable in our study areas, and whether or not they pose a threat to native E. angustifolia in our remnants. We have returned to the plot each of the last three years to measure number of rosettes and leaf lengths of these plants.

Table 1 shows the number of plants found alive during each search. These plants were measured on August 4th and rechecked on August 23rd. No plants flowered this year, although there were several found that had leaves over 40cm long.

| Year / Event |

Number Alive |

% Original remaining |

% Of prev. year |

| Planting (2014) |

746 |

100 |

|

| 2014 |

638 |

85.5 |

85.5 |

| 2015 |

521 |

69.8 |

81.7 |

| 2016 |

493 |

66.1 |

94.6 |

Start year: 2014

Location: Hegg Lake Wildlife Management Area — experimental plot 9

Overlapping experiments: Echinacea hybrids — experimental plot 6, Echinacea hybrids — experimental plot 7

Data collected: Rosette number, length of all leaves, herbivory for each plant collected electronically and exported to CGData. Recheck information for plants not found was also collected electronically and stored in CGData.

You can find out more information about experimental plot 9 and flog posts mentioning the experiment on the background page for the experiment.

Counting the fruit of a flowering plant. In 2009 and 2010, porcupine grass (Hesperostipa spartea, a.k.a. “stipa”) was planted in experimental plot 1. In total, 4417 seeds were planted, 1 m apart, 10 cm north of Echinacea plants. Between 2010 and 2013, each position was checked, and the plant status recorded. Since 2014, we have only searched for flowering plants. This summer, 143 flowering stipa were found, with a median of 24 fruit per plant. We also checked for living plants in positions where stipa was observed in 2011 or 2014. In these additional 492 positions, 89 plants were found alive, with 19 of those plants flowering.

The following table shows how many plants have been found alive in each year.

| Year |

Found |

Flowering |

Full Fruit |

| 2010* |

702 |

|

|

| 2011 |

483 |

|

|

| 2013 |

442 |

4 |

|

| 2014** |

32 |

32 |

199 |

| 2015*** |

26 |

1 |

9 |

| 2016**** |

208 |

143 |

4391 |

(*) only one cohort (2009) included, (**) only searched for flowering plants, (***) only searched prior year’s flowering plants, (****) only searched flowering plants + subset of positions

Start year: 2009

Location: Experimental plot 1

Physical specimens: Fruits from 127 flowering plants, currently stored at the lab in Chicago. These may be used in a future study on traits of stipa‘s awns.

Data collected:

- Culm count and number of fruits recorded on visors (backed up to CGData)

- Fruit harvest information recorded on paper (stored at Hjelm house)

- Status of 2011 basal plants recorded on visors (backed up to as “2016stipaRecheck2011positions” in CGData)

Products:

- Josh Drizin’s MS thesis included a section on the hygroscopicity (reaction to humidity) of stipa awns. View his presentation or watch his short video.

- Joseph Campagna and Jamie Sauer (Lake Forest College) did a report on variation in stipa’s physical traits within and among families in 2009

You can find out more about stipa in the common garden and links to previous flog posts about this project on the background page for this experiment.

Ants tending Aphis echinaceae Aphis echinaceae is a specialist aphid that is found only on Echinacea angustifolia. It feeds on sap in Echinacea leaves, and can also be found on flowering heads. This aphid also attracts “ant bodyguards”, which protect the aphids from predation, and in the process may also fend off other potential herbivores. Prior studies by Team Echinacea members have demonstrated that aphid presence does not lead to significant changes in plant fitness in observational studies, although in controlled experiments aphid presence does affect herbivore damage. Furthermore, inbred plants are more susceptible to aphid presence than outbred plants.

In 2011, Katherine Muller designated a sample of 100 plants in experimental plot 1 for aphid addition or removal. The presence or absence of these aphids is maintained by team members two to three times per week. In summer 2016, aphid levels were assessed and maintained 14 times on 70 of these plants (addition on 33, exclusion on 37) from early July until early August. In September, Amy Waananen recorded signs of senescence in the leaves of treatment plants. This data can be combined with data from our common garden measuring data to explore the richness of the Echinacea-aphid relationship.

Start year: 2011

Location: Experimental Plot 1

Overlaps with: Phenology and fitness in P1

Data collected:

- Aphid counts for each treatment plant on each observation day, on paper

- Leaf senescence data, recorded on paper

- Initial and final assessment of aphid counts on treatment plants, recorded on paper

- Paper records stored in ‘Aphids 2016’ binder, currently at Chicago Botanic Garden

- Aphid counts also included in p1 measuring data

Products:

- 2016 paper by Katherine Muller and Stuart on aphids and foliar herbivory damage on Echinacea

- 2015 paper by Ruth Shaw and Stuart on fitness and demographic consequences of aphid loads

- 2015 poster by Daniel Brown and Kyle Silverhus (Lake Forest College) on achene and seed set differences on treatment plants

You can read more about the aphid addition and exclusion experiment, as well as links to prior flog entries mentioning the experiment, on the background page for this experiment.

Echinacea Pallida at Hegg Lake Although originally used as part of Josh Drizin’s experiment with exotic grasses, this plot also has hybrids of Echinacea angustifolia and Echinacea pallida. Gretel and Nicholas Goldsmith performed reciprocal crosses between 5 non-native pallida plants found at Hegg Lake and 31 angustifolia plants in P1 and planted 66 seedlings between grasses in 2012. These plants have been revisited each summer since then. This year, on August 3rd, Laura Leventhal and I found 36 of the original 66 plants – a sharp decline from the 55 found last year. This means that 55% of the original cohort is still alive, with the survival rate this winter of 65%. Of the surviving plants, only three had more than one rosette.

Year started: Crossing in 2011, planting in 2012

Location: Experimental Plot 6, on Tower Road

Overlaps with: Echinacea hybrids — ex Pt 7, Echinacea hybrids — ex Pt 9

Data collected: Status, rosette count, longest leaf measurement, and number of leaves for each plant. Exported to CGData.

Products: Nicholas Goldsmith’s summary of the crossing done in 2011 can be found here.

You can find more information about experimental plot 6 and previous flog posts about it on the background page for the experiment.

|

|