Today, Drake gave a great talk titled “Investigating the effects of parasitic plants in tallgrass prairies” for the Plant Science Department at the Chicago Botanic Garden. We enjoyed hearing an update on his research and peeking at some preliminary results! According to Lindsey, “The talk was pedicularily riveting and he really comandra’d the room. Drake is producing cuscuting-edge science. His research agalinis with broader conservation and restoration goals in the tallgrass prairie.”

|

||||||||||

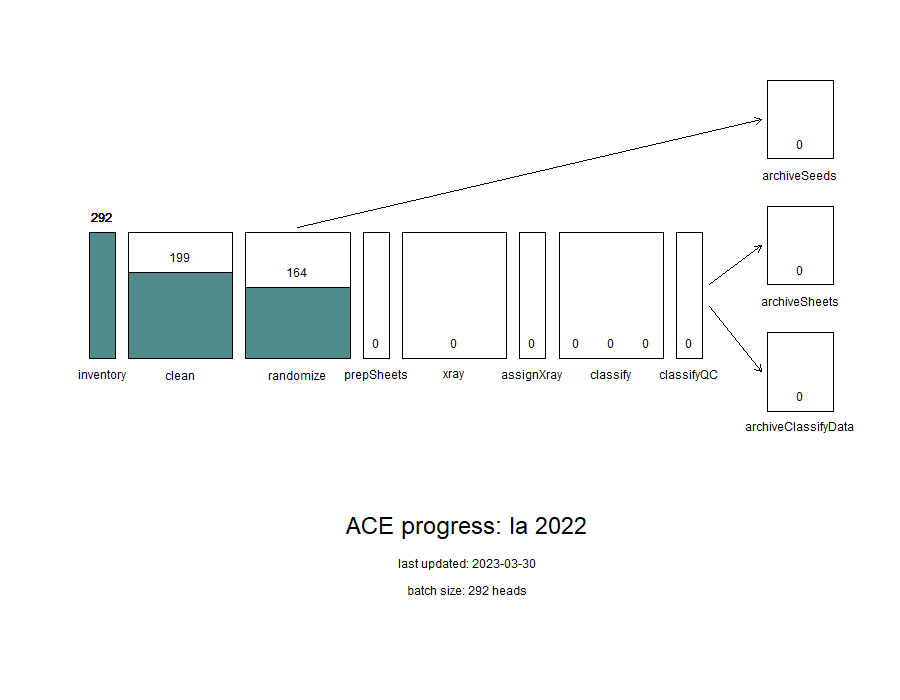

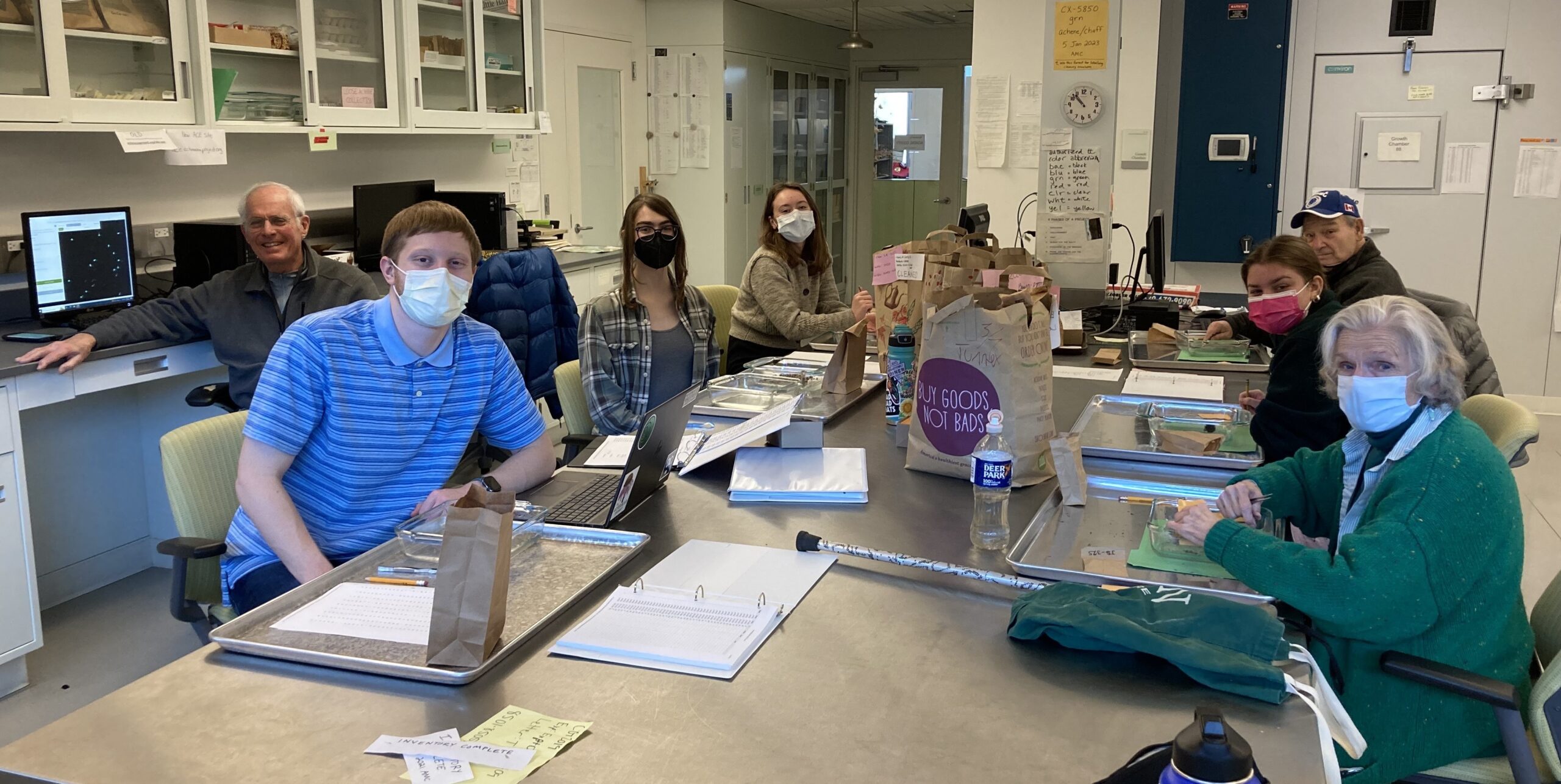

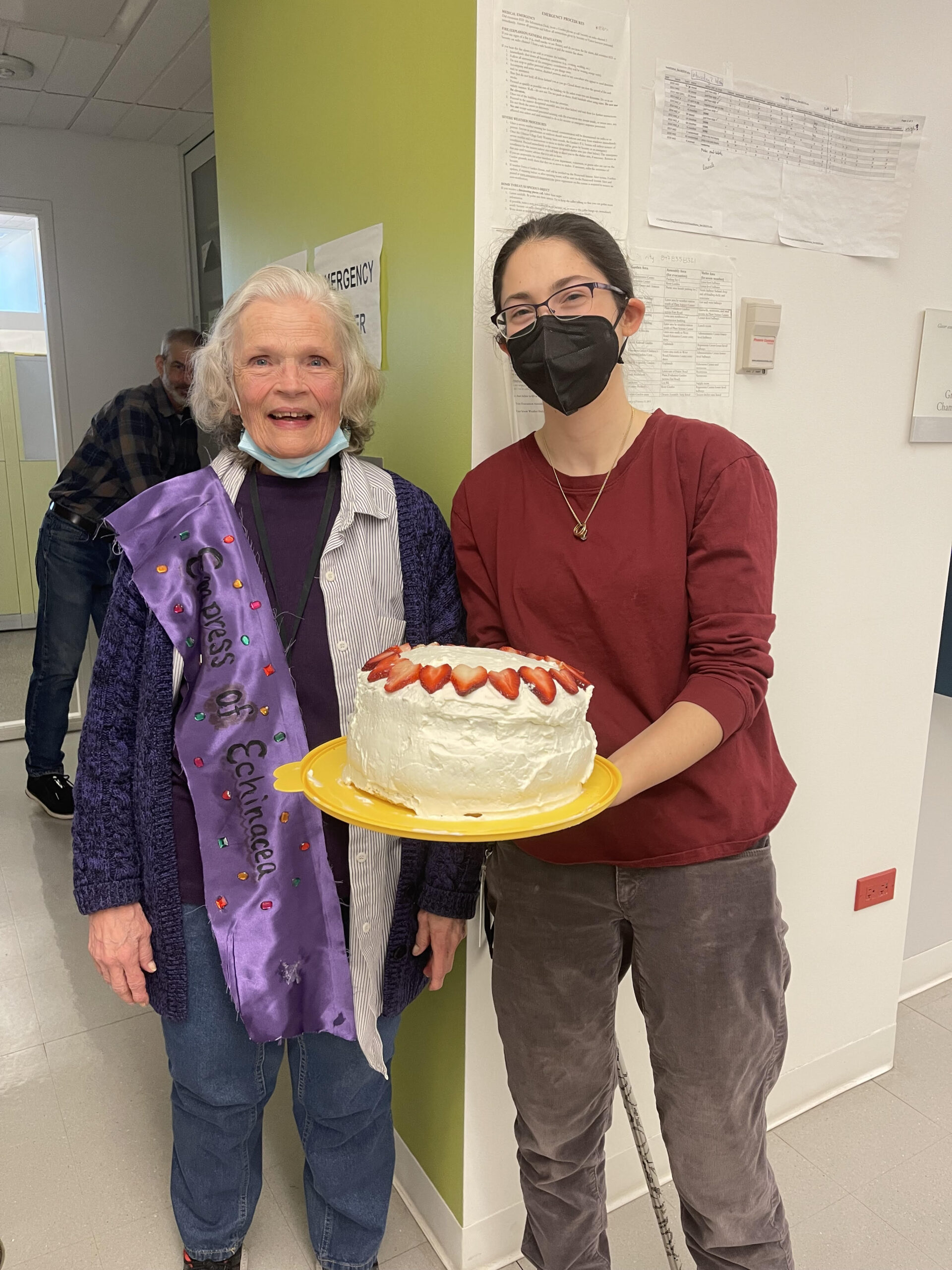

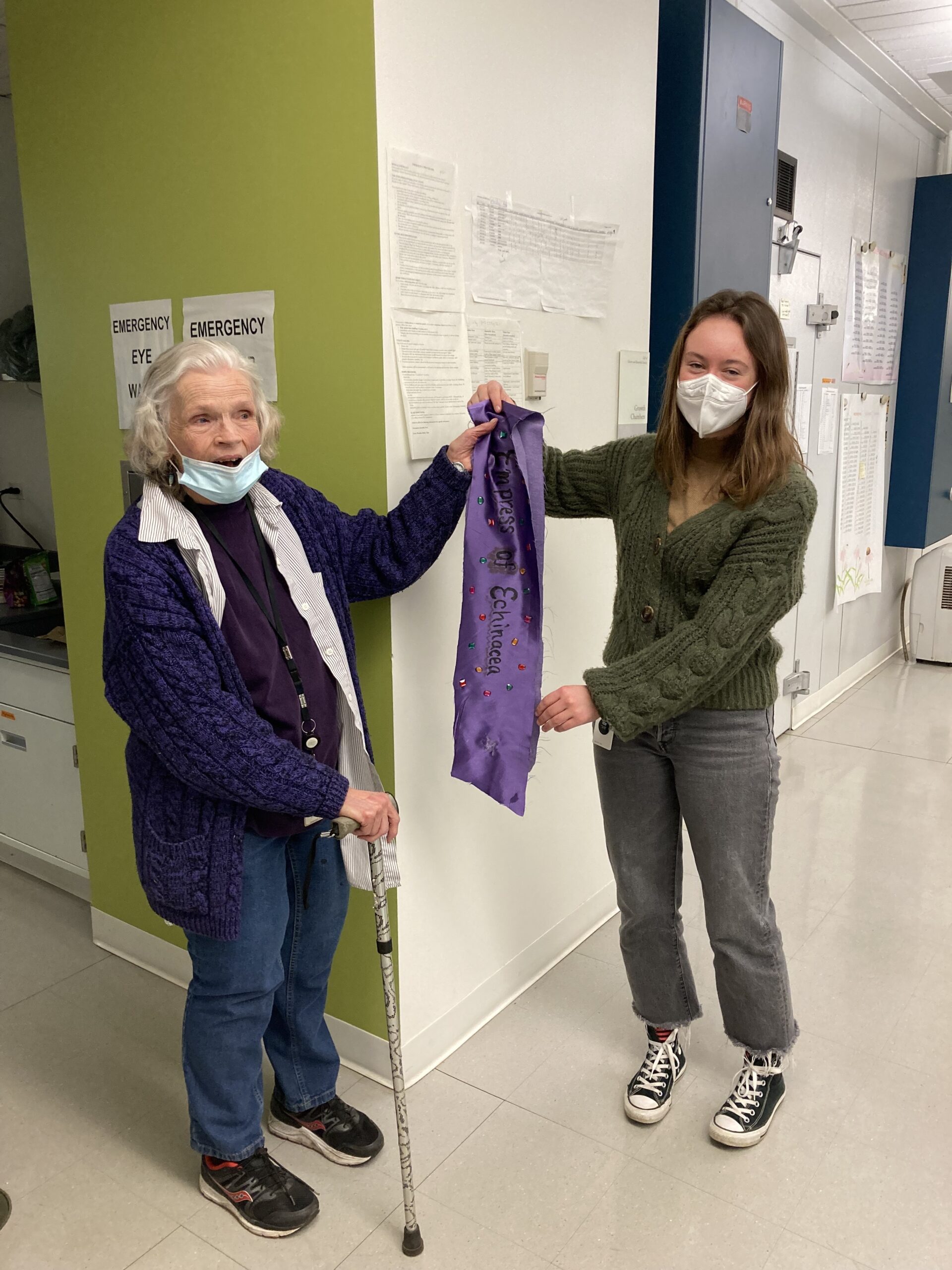

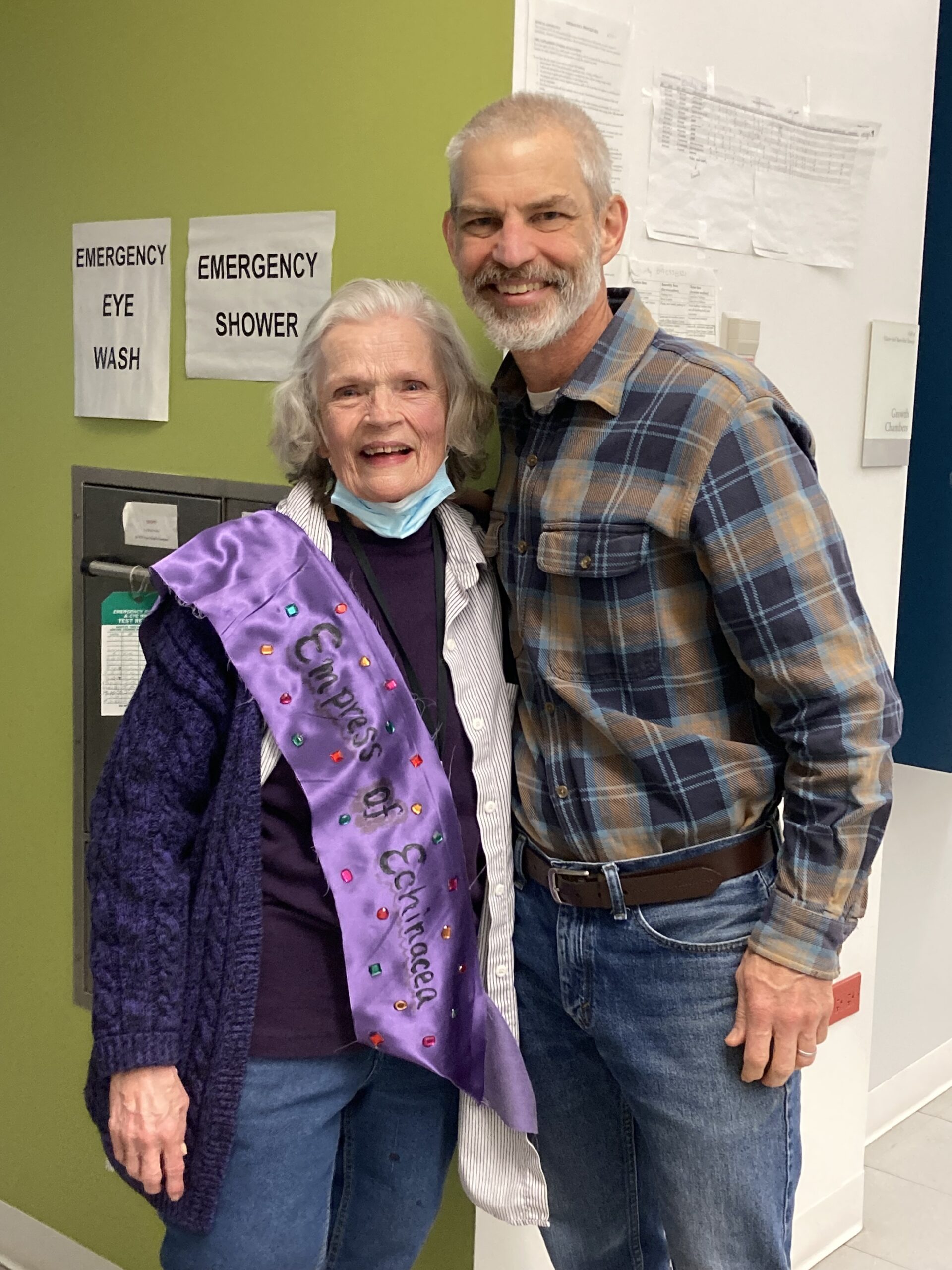

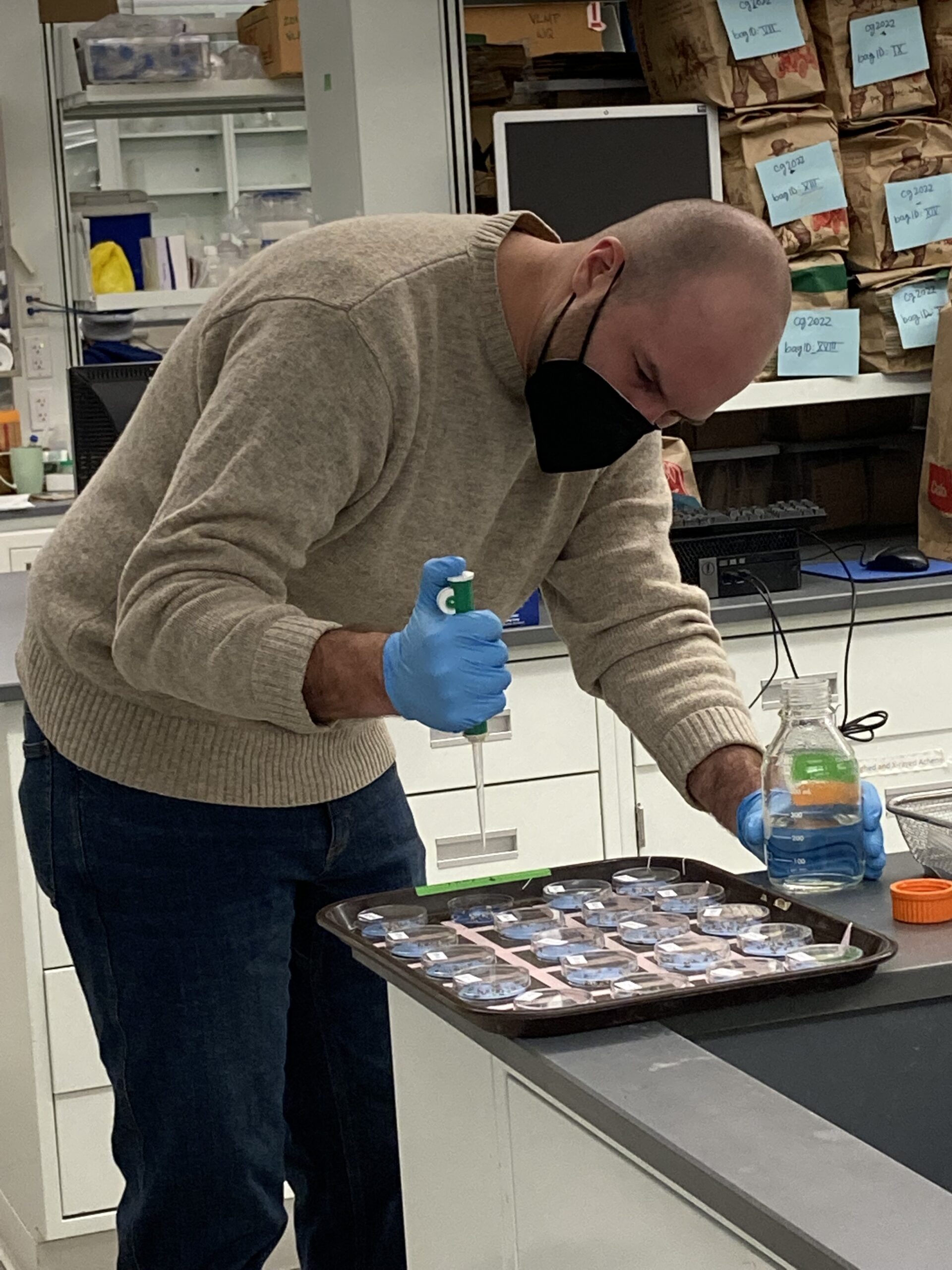

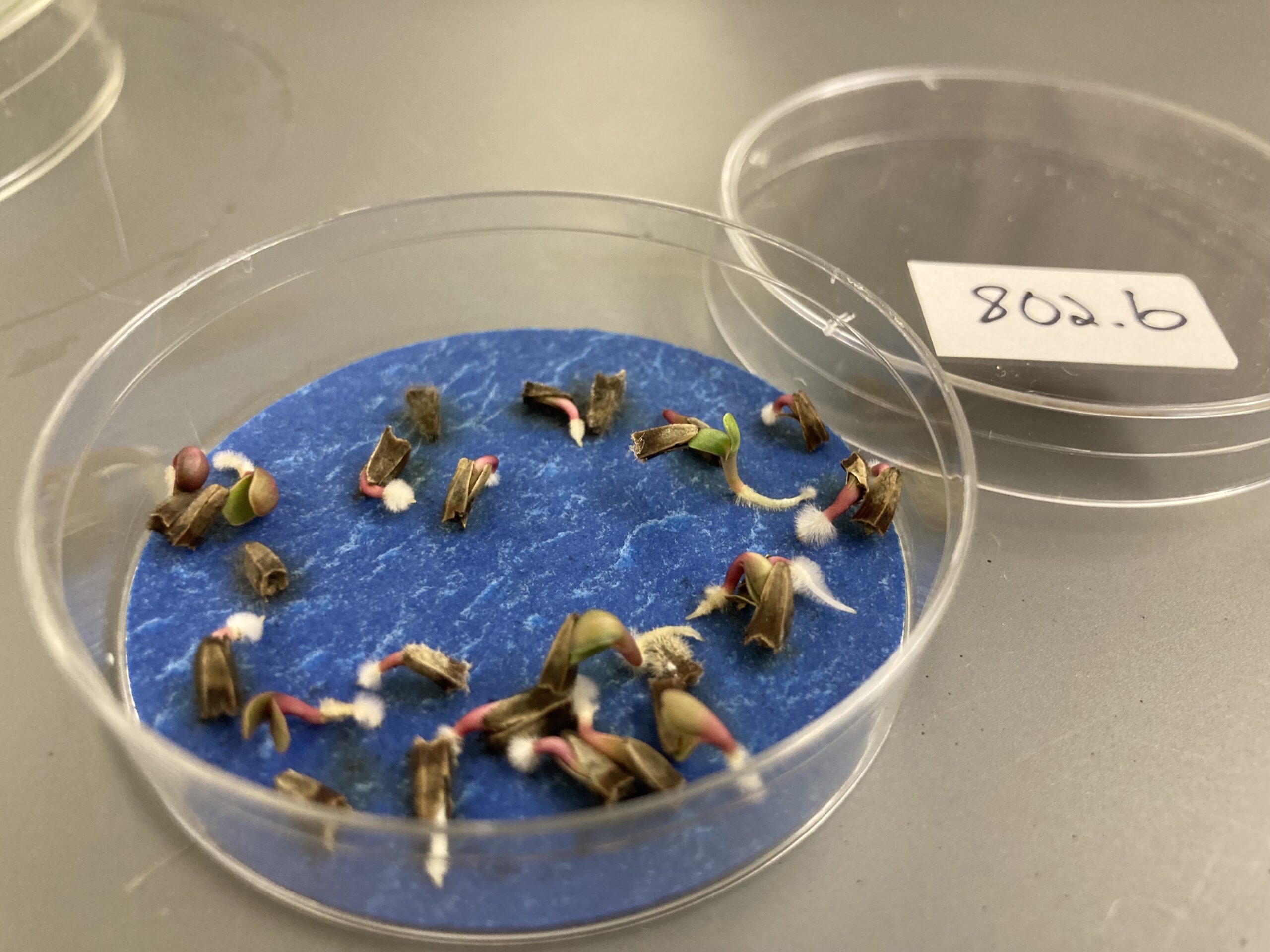

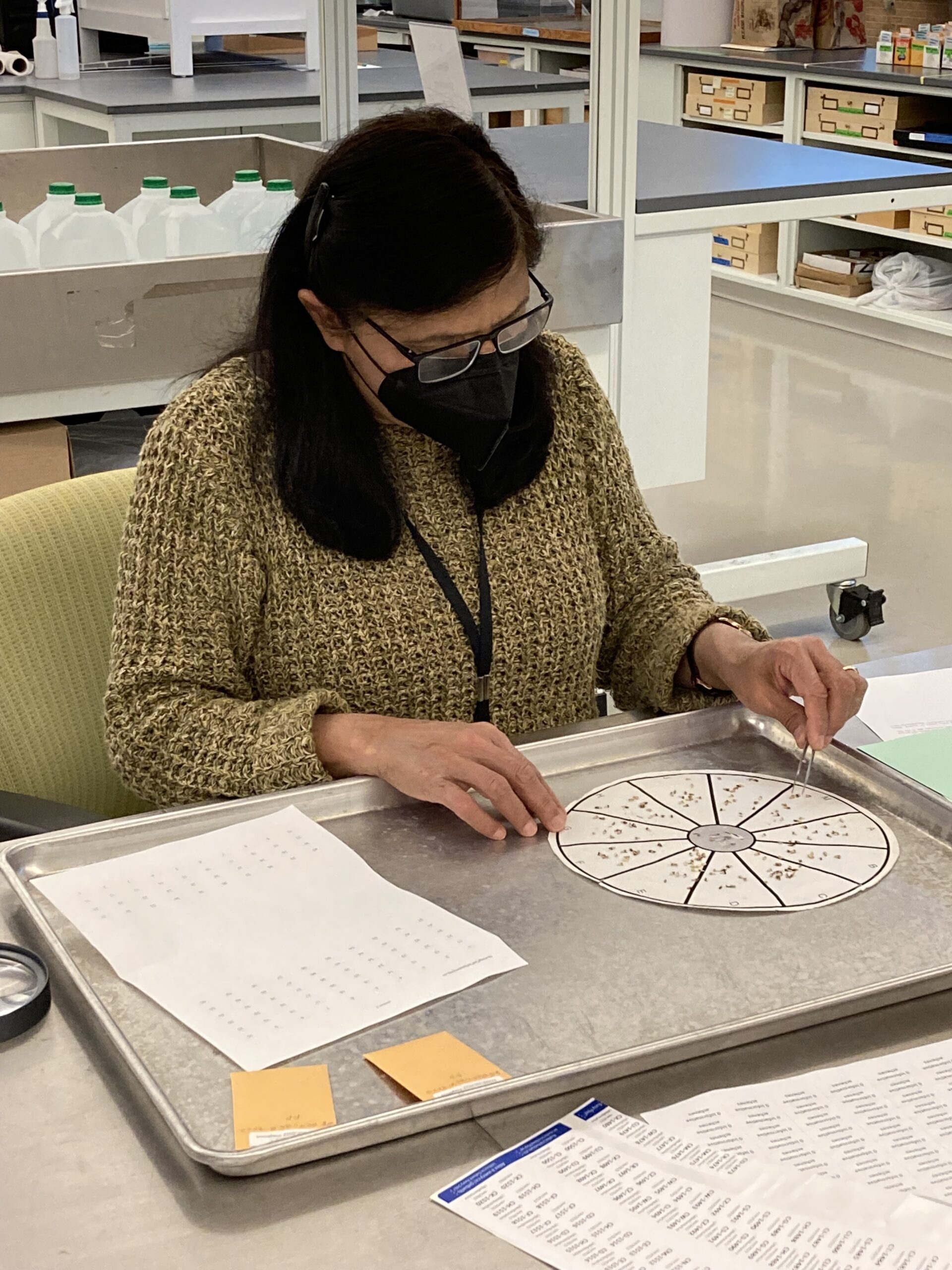

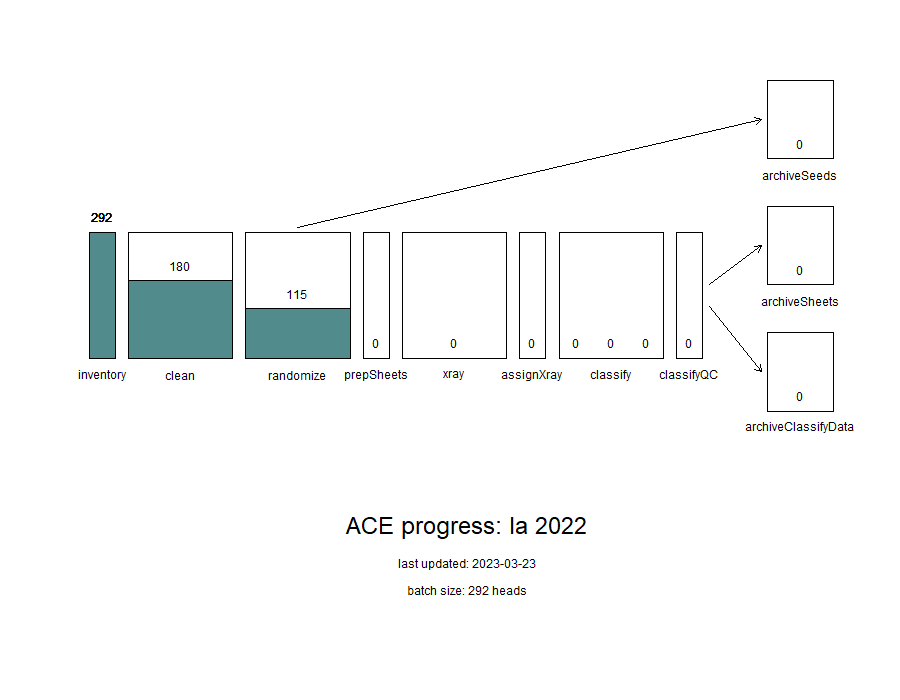

We are so close! We are now a little over two-thirds of the way done with the third batch, and things are starting to get exciting. I want to thank those who helped with randomizing; we would not have gotten this far without your help. With that said, there are now less than 20 plants left to randomize, and we are just about ready to move on to the data entry and interpretation steps. We should have randomization wrapped up by next week, so we should hopefully have our results in by next week. After that, we will then analyze the final results and begin to construct a final poster. More details will be provided for the poster, but in the meantime, we are quite excited about the next steps once randomization is complete.  Things are movin’ and groovin’ in the lab at the Chicago Botanic Garden! Now that we’ve wrapped up remnant Echinacea, it’s time to reenter common garden territory. Ah, sweet sweet common garden, where all plants exist neatly* on a grid unlike the unruly remnants. One of the main things we’ve been tackling is cleaning the 2022 common garden heads. There are 2,116 heads to be cleaned and we’ve already cleaned 561 (or ~27%) of them! Wow, amazing progress! The only remaining and 3 additional bags from 2020. Once those are done, we’re caught up from the backlog that COVID augmented. As for other steps in the ACE process…  After cleaning comes rechecking, and we’ve had students working on rechecking Echinacea heads from experimental plot 1 in 2019 and 2020. Once these have been rechecked, we’ve got scan-master volunteer Marty prepare our achenes for uploading to the ACE website! Our volunteers have also been catching us up on counting from 2017 through 2019 to get data ready for Wyatt’s masters thesis! I won’t spoil what she’s investigating, but just know it’s a burning question that I’m stoked about! Alex and I have also been attempting to clean up the Cheerios boxes that line our lab window. These boxes contain achenes from the past 20 years and many different experiments, all at different stages of the ACE process. Volunteers have started assembling some of the achenes into x-ray sheets for the years 2017 and 2018. We also had Priti help us inventory boxes from 2016. We took seeds out of these boxes for our seed addition experiment, but were unsure what achenes actually remained. These seeds did not germinate, so we will put them in storage. However, we have other seeds that are still viable, so we are hoping to freeze them and put them in the seed bank here at CBG!  We’re hoping to keep moving forward this spring with all steps of the ACE process, and create an efficient system for taking data off the ACE counting and classifying website! *it would be neatly if it weren’t for those meddling rogue plants! On the final Tuesday of March, the Echinacea Project honored our most recent inductee to the Achene County royal court. One of our loyal volunteers, Char Schweingruber, was crowned the Empress of Echinacea! This is a prestigious title reserved for a citizen who has demonstrated a longtime dedication to the lab, a mastery of cleaning Echinacea heads and a passion for conservation and restoration.   Char has been a volunteer at CBG since 1993. She began much of her volunteer career outdoors doing restoration work in the natural areas of the garden, especially in our beloved prairie ecosystem! She has been involved in the Echinacea Project since its inception when Stuart began at the garden in 2001. She joined a small group of volunteers that spearheaded our ACE protocol where Echinacea seeds are cleaned, counted and assessed for pollination rates. These days, Char is an expert at cleaning Echinacea heads and is essential in keeping our lab process moving. We appreciate our volunteers, like Char, who dedicate their time to the Echinacea Project!  The ceremony involved a speech from Stuart, the conferring of the royal sash, and a delicious strawberry layer cake baked fresh by Alex! As Tuesdays are the day where we have the most volunteers in the lab, it was great to celebrate all of Char’s hard work with a large group of volunteers and CBG staff members.  If you see Char walking in the halls of the Plant Science building, don’t forget to congratulate her on her new title (and maybe give a proper bow or curtsy, if you feel inclined)! In fall 2022, we planted Echinacea within our study site for the seed addition experiment. In the lab, we are currently doing a germination experiment with the same batch of seeds to calculate the expected seed germination rates under ideal conditions. Following our standard germination protocol, we first treat the achenes with Florel solution and put them in a cold fridge with low light levels to mimic winter conditions. After 14 days, we transfer them to a warm, bright environment to germinate.    The seeds generally don’t start to germinate until they are in the warm environment. This year, however, I checked on the seeds a few days after they went into the fridge and discovered that they were already starting to sprout! The condenser on the fridge had broken, so it was no colder than room temperature. In spite of the unusual conditions, ~80% of the seeds germinated. This is very encouraging since it means that the seeds that we planted in the fall were viable. After fixing the fridge, we are germinating a second batch of seeds following the standard protocol so we can replicate the experiment next spring. Lindsey planted the seeds that germinated, and we plan to grow them into plugs and transplant them this summer. This February, Lindsey and I attended the Chicago Wilderness prescription burn training at the Morton Arboretum. This month, we put our burn training to good use and joined Jared and the burn crew at the Chicago Botanic Garden for a woodland burn. I participated in prairie burns in Minnesota last spring, but this was my first woodland burn, so I was glad to gain more diverse fire experience. We burned part of McDonald woods on the east side of the garden, and we needed an east wind to keep the smoke off of Green Bay Road. The wind was ~11 mph, but we were burning down in a gully which blocked the wind, so the fire crept very slowly. Overall, the woodland burn was much slower and patchier than the past prairie burns, but that was what I expected from the woods. I also got to use a drip torch for the first time, which was very fun!   Orchids in a ball, orchids on a post, orchids in a spiral, orchids in the water, orchids in a pot, orchids through a lens. How many ways can you imagine displaying an orchid? This week, Lindsey and I visited Orchids Magnified at the Botanic Garden, and we saw orchids in all these orientations and many more. I was amazed by the orchids’ astonishing range of color and shape. It makes me wonder about their evolutionary history.          The orchid show staff night also included free food. Lindsey tried the ramen, and she reported, “It had many tasty vegetables and the teeniest mushrooms. However, it could have used some spice and they only had forks”. I sampled the salad, which contained an orchid flower. It felt wrong to eat one after looking at so many, but I had to try it. I expected a flowery flavor like jasmine, but it was rather bland and not much different in taste from a lettuce leaf. In short, I don’t recommend snacking on orchids if you attend the show. One of our main goals over the past two years has been to process all of the Echinacea harvested from remnants in 2020, 2021, and 2022 to investigate the effects of prescribed fire on flowering and fitness. We harvested 1,012 heads over these three years.

For each head, the end goal is to get an accurate count of the number of achenes and the seed set, a measure of pollination success. To collect these data, we sent the Echinacea through our high-throughput seed processing system, which we call the ACE process. (The true meaning of ACE is controversial: Always Cleaning Echinacea? Accurately Counting Echinacea? Achene Chaos Extraordinaire?) The ACE process has many steps: inventory, clean, recheck, scan, count, randomize, x-ray, classify, store. In spring 2023, we finished processing all of the remnant Echinacea from 2020, 2021, and 2022! We send a huge thank you to all the students and volunteers who put in many hours on this project over the last few years. We couldn’t have done it without you!        Jared is currently adding the achene count and seed set data to the remnant data repository on the Echinacea Project website. All achenes are currently in the dehumidifier at the Chicago Botanic Garden. After two weeks of drying, they can be stored in the seed bank.  I know it has been a while since I last gave you all an update, but we have some good news to share! We managed to finish cleaning the third batch and are close to completing randomization for the second batch. I will say our progress has been pretty steady before the last update I shared with you, but we decided to out some ways to accelerate processes, such as randomization. We created an assembly line (shown in the image above). We tasked people to either set up the stations by pouring and spreading out the achenes onto the randomization grids or randomly select grids in which achenes will be inspected for predation. We found this setup to be much more efficient, and hopefully, by the end of next week, we may have three batches fully cleaned and randomized. However, our initial goal of completing five batches may be somewhat too ambitious, so instead, we decided to just focus on three batches so there may be time to collect and analyze the data. In the figure below, you will find our overall progress made on the project, and given that my focus would be on studying predation rates on Liatris plants, the stuff that comes after randomization does not necessarily apply to the findings I will need. With that said, those other sets of data will most likely be of use for other studies, and the Echinacea Project will most certainly take a look into those things. Overall, things are looking good for us with the project, and I cannot wait to see the results soon.  P.S., I did not have a chance to specifically address my project’s intentions in an ABT prompt, so here it is: “We know that Liatris plants get eaten more often than Echinacea plants, and predation rates tend to be higher in the absence of fires, but we do not know which types of which types of Liatris plants may be more likely to be eaten than others. Therefore, we are studying how the number heads of a Liatris plant affects the predation rate on the plant’s achenes.” Pollinators are declining worldwide, a phenomenon that some people are calling the insect apocalypse. There are many factors driving these population declines, and loss of habitat has been identified as one major cause of insect demise. In our study area in western Minnesota, we have seen numerous prairie patches converted to agriculture over the years. However, we don’t know how the bee community has changed over time across the landscape. To investigate these questions, the Echinacea Project started the Pollinators on Roadsides project back in 2004, and we collected another year of data this past summer. In the fall, we brought 7 coolers of insects back to the lab at the Chicago Botanic Garden. This winter and spring, volunteer Mike has been busy as a bee pinning all the specimens so we can send them to Zach Portman, a bee taxonomist at the University of Minnesota. This week, Mike started working on the last cooler of bees! So far, he’s pinned 680 insects collected in 2022.   Funding for this project was provided by the Minnesota Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund as recommended by the Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources (LCCMR). The Trust Fund is a permanent fund constitutionally established by the citizens of Minnesota to assist in the protection, conservation, preservation, and enhancement of the state’s air, water, land, fish, wildlife, and other natural resources. |

||||||||||

|

© 2024 The Echinacea Project - All Rights Reserved - Log in Powered by WordPress & Atahualpa |

||||||||||